This post is part of a series of weekly case studies addressing legislative approaches to rape in the EU. They are taken from a report written by our research associate, Nathalie Greenfield, which was made fully available on our website (along with a complete bibliography of works cited) on June 17th 2019.

The EU comprises 27 EU Member States, 21 of which have ratified the Istanbul Convention and all of which are contracting member states of the ECHR. Few have national rape legislation that complies with the international standards outlined in comprehensive and important legal instruments, despite their obligations under both the Istanbul Convention and the ECtHR’s binding interpretations of the ECHR.

One of the most important sticking points is the definition of rape. As outlined in Part One, comprehensive international guidelines and treaties call for consent-based standards in rape and sexual assault legislation, yet only seven EU Member States have legislation that defines rape based on consent. International instruments also outline the need for tailored victim support services, yet not all Member States have adequate provision for victims. Specifically, the Istanbul Convention requires rape to be defined as a violation of bodily autonomy, yet the language of morality and decency persists in some countries’ definitions of the crime. Europe has work to do.

Importantly, there are some examples of good practice among Member States. Sweden’s new approach is one to watch; victim-centred and responsive to civil society advocacy, Sweden’s model will show in the years to come how a consent-based approach can be implemented in a civil law jurisdiction. As regards common law jurisdictions, the UK provides a good legal standard, despite not having ratified the Istanbul Convention.

Having an affirmative consent-based standard for rape is critical. This standard provides a threshold for rape that responds to trends in contemporary moral thinking on sexual violence. Introducing elements of force, violence, threat, or power into the definition of rape creates room for courts to misinterpret these elements, and compels victims to show resistance to such force or threats in order to carry the burden of her case. Force, violence, threat, and abuse of power can be evidence of non-consent, but should not be per se elements of rape. Indeed, the ECtHR has noted that “there is a universal trend towards regarding lack of consent as the essential element of rape and sexual abuse [and] the evolution of societies towards effective equality and respect for each individual’s sexual autonomy”[1] – let us embrace this trend. Consent is at the heart of what constitutes rape; consent should be the baseline definition for rape.

To achieve this, countries must bring their national legislation in line with the instruments that bind them: treaties such as the Istanbul Convention, and international tribunals such as the ECtHR. Another path to achieving this goal is through a legally binding instrument at EU level. The EU has recognised its current lack of authority in this domain, which suggests the need for corrective action:

“At the moment, the EU policy against violence against women at large is based on Council conclusions, resolutions of the Parliament, and Commission strategies. However, none of these documents are legal instruments which bind the Member States to make a change for women.”[2]

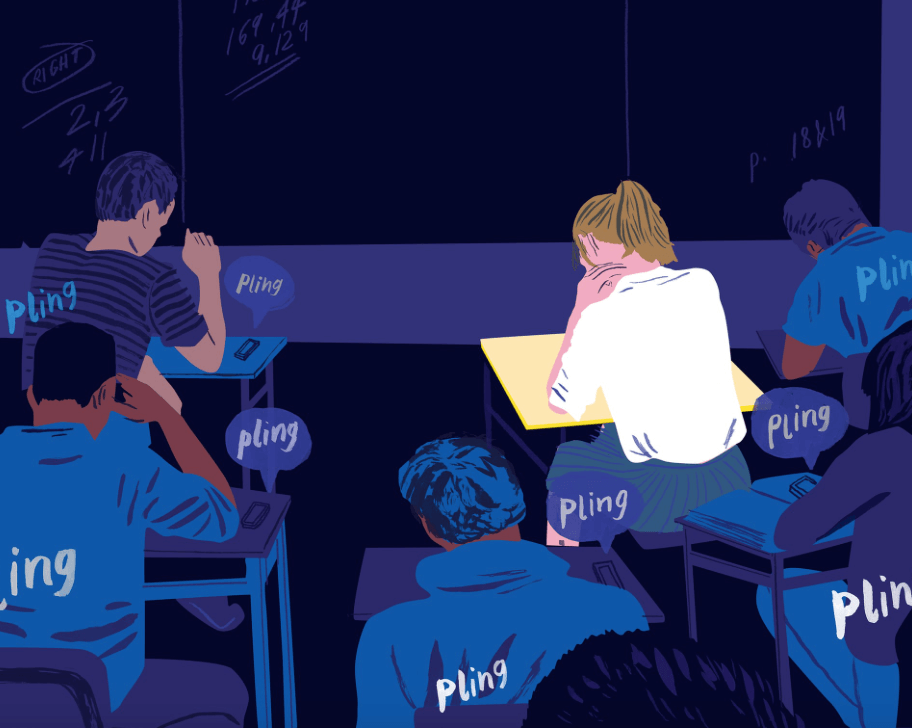

It must not be forgotten that legislation is but a step in effectively tackling violence against women. There is gap between what the law requires, and how police and prosecutors choose to go forward. The road from first reporting a rape to seeing a conviction is long and complex in all countries, with many stages at which a case can be abandoned or fall apart. With respect to legal definitions, the law might not need a showing of force or resistance on the part of the victim but prosecutors typically won’t choose to go forward in the absence of these elements. Legislation is important, but a multifaceted approach to criminal justice in this field is essential to tackling the endemic levels of rape and violence against women in Europe.

[1] M.C. v. Bulgaria, ¶163

[2] European Parliament DG IPOL, p.41