TW: references to sexual violence and abuse and gender binary.

Women are about twice as likely as men to develop depression (Kuehner C 2003), which is a very disabling disease. But, how can we explain the gender gap in depression?

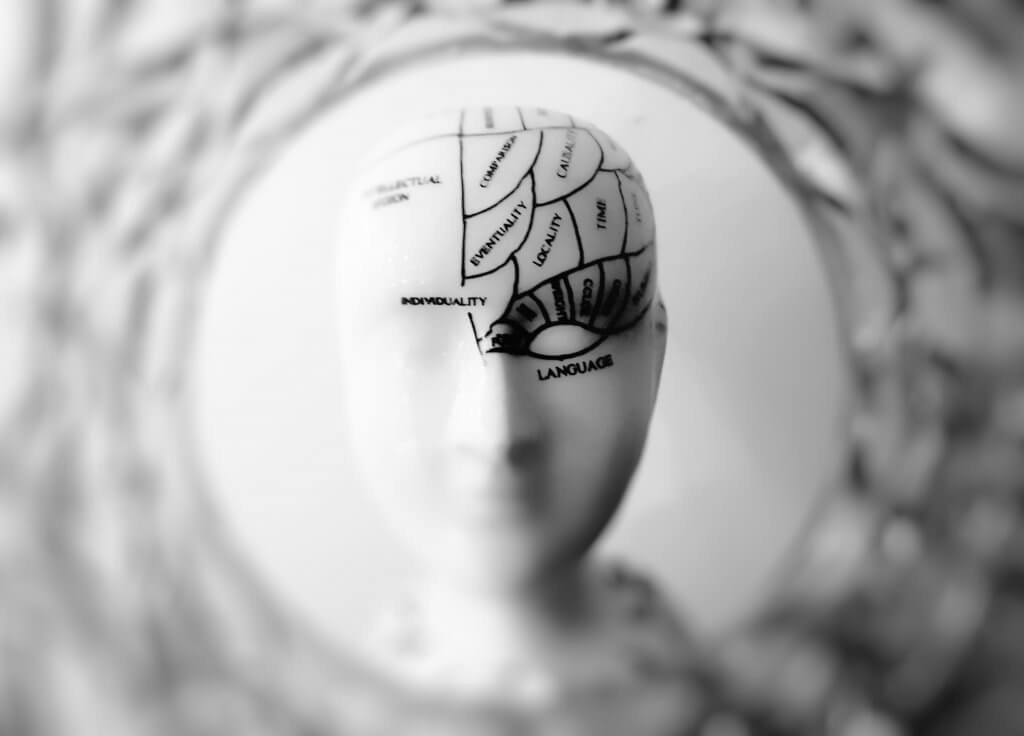

Would it be because of a difference between “female” and “male” brain? By exploring cutting-edge neuroscience, the neuroscientist Gina Rippon claimed the need to move beyond this binary view of brains , suggesting that we need to see them as highly individualised and profoundly adaptable (Rippon G. 2019). Human brain development is not just a biological matter: other factors influence it, including “gender”. Epigenetic studies have highlighted that genes predisposed to mental health disorders could be modulated by environmental factors and phenotypically express as ‘internalising or externalising disorders, according to gender’ (Kuehner C. 2017).

Sexual hormones are believed to contribute to the gender gap in depression. Recent evidence suggests that a variation in the levels of ovarian hormones, especially the reduction of estrogens, may contribute to the prevalence of depression and anxiety in women (Albert P.R. 2015). However, other factors seem to interact with hormones. For example, female adolescents’ high susceptibility to depression could be mainly linked to the interaction of sex hormones with intrapersonal and interpersonal factors, such as a negative self-perception due to body changes, stress related to puberty, even sexual abuse (Kuehner C. 2003, Graber J.A. 2013). Could it be possible that, in a (Western) society where the “dominant observing eye” is male, the physical change that occurs during puberty would expose girls to distress and embarrassment, as well as to the sense of a loss of control on their own bodies which are sexualised and objectified? Then, to what extent do feelings of judgement and pressure increase the risk of body dissatisfaction and discomfort in interpersonal relationships?

Another factor to be considered is ‘neuroticism’, a personality trait defined as a tendency towards negative feelings following frustrations and stress. Neuroticism is a recognised risk factor for depression (Klein D.N. 2011), and females score higher in neuroticism than males (Costa P.T. Jr 2001). May this have something to do with the gendered education of children? During childhood, for instance, girls show a conspicuous tendency to self-control and impulse inhibition compared to boys (Else-Quest N.M. 2006) and low self-esteem and insecurity (Bian L. 2017).

A fundamental determinant for women’s health is gender violence, which is recognised not only as a human’s rights violation but also as a global health problem (UN General Assembly 1979, Council of Europe 2011). Women who are victims of violence are twice as likely to experience depression (WHO 2013). Interesting evidence is that psychological domestic violence can be as damaging for mental health as physical violence (Pico-Alfonso M.A. 2006). International guidelines (WHO, NICE) recommend that mental health professionals are adequately trained about this issue and facilitate the disclosure of domestic violence, offer support and safety, avoid pathologising and medicalising suffering, provide treatment for physical and mental disorders resulting from violence (WHO 2013, NICE 2014). Some studies (Humphreys C. 2003, Trevillion K. 2014) have found that, in the context of violence, psychiatric symptoms could be better interpreted as understandable chronic anxiety of further abuses, even if they satisfy the criteria for a mental health disorder diagnosis.

Social determinants of health must therefore be considered in contributing to the gender gap in depression. The levels of gender equity in a society, which are measured as political participation, economic autonomy and reproductive rights, have an effect on the gender gap in depression. In the USA, women living in states with lower gender equity showed higher depressive symptoms than women living in states with better gender equity (Chen Y.Y. 2005). Same results were found in Europe (Van de Velde S. 2013). Social determinants don’t act as independent factors but interact with each other to affect health; therefore, intersectionality (Crenshaw K. 1989) must be always practised. In general, poverty is a social determinant influencing negatively mental health. Moreover, many factors are responsible for the feminization of poverty: fthe gender pay gap, reduced number of women at the leadership job positions, unpaid care work, and women’s employment discontinuity (Freixas A. 2012). Being employed generally represents a protective factor for mental health. However, a study on a sample of Dutch adults (Plaisier I. 2008) showed that paid work was a protective factor for the development of depression among all men and among women but without children. Although the increased number of women working, the sharing of housework remained often unchanged. Performing multiple social roles, which is characteristic of the so-called ‘ female condition’, causes stress and responsibility overload that negatively affect women’s mental health (Bambra C. 2009). A study on a sample of Canadian women (Glynn K. 2009) highlighted a negative correlation between role overload and mental well-being, more significant than that of other social determinants. With regards to paid job, a report in the UK carried out over a 3 year period (2014-2017) showed that the prevalence of job-related stress, depression and anxiety, was statistically superior among women than among men (Health and Safety Executive 2017). It is not surprising due to the striking discrepancy between women and men in the workplace (World Economic Forum 2017).

Alongside this, women experience a higher percentage of episodes of everyday sexism than men, being everywhere victims of comments and behaviours that reflect and strengthen gender stereotypes, degrading and humiliating comments and behaviours, sexist language, sexual objectification (Swin J.K. 2001). Everyday sexism negatively affects women’s psychological well being, causing feelings of anger, discomfort, sadness, anxiety, low self-esteem (Swim J.K. 2001) and increasing stress, anxiety and depression (Foster M.D. 2000, Borrell C. 2011). In addition, a moderately strong relationship between the experience of everyday sexism and post-traumatic stress disorder in women was reported (Berg S.H. 2006). The perceptions of gender discrimination partially explained the gap between working men’s and women’s mental health in the United States (Harnois C.E. 2018). Everyday sexism produces a chronic perception of being discriminated and constantly judged, therefore undermines self-esteem, causes social anxiety, determines chronic stress with a further weakening of mental health. In addition, since everyday sexism is widespread and repeatedly perpetrated, can be interiorised and affect women’s sense of agency. Benevolent sexism, which is often unnoticed, must be tackled too.

It must be said that a psychiatric gender-sensitive evaluation may increase the diagnosis of depression among men (Cavanagh A. 2017). It is recognised that depressed males are more likely to report externalised symptoms, such as alcohol abuse, substance abuse, reduced impulse control, risky behaviours. Social expectations, different for women and men, play a role in the perception and expression of depressive symptoms; for instance, depressed men may consider alcohol or substance abuse as a more gender-appropriate way to express suffering than cry or being sad (Ridge D. 2011). Furthermore, it is known a general scarce men’s tendency to seek professional help at mental health service (Pederson E.L. 2007, Gouwy A. 2008). Among men, levels of stigma for seeking professional mental health help is high in terms of both social and personal stigma (Nam S.K. 2013, Vogel D.L., 2011). This could be related to traditional gender norms which would encourage men to repress mental health problems, reduce emotional expression, considering asking for help as a feminine activity and a sign of weakness and lack of virility (Johnson J.L. 2012). Even women “perform” gender norms giving different advice depending on sex. Moreover, it seems that the patient’s gender would influence the diagnosis and treatment proposed by (female and male) doctors (Loring M. 1988).

The “gender gap” in depression should be interpreted according to a multifactorial perspective, in which social determinants, psychological factors and socialisation process play an important role. The gender factor itself, which is prescriptive and normative, affects mental health. An interesting theory (Bem S.L. 1974) showed that people who were able to move from “masculine” to “feminine” behaviours depending to contexts, called “androgyny”, were psychologically more adaptive than people who strictly align to stereotypes of masculinity and femininity. A study (Juster R.P. 2016) found that androgyny people reported higher self-esteem and well-being as well as less depressive symptoms, regardless of sex. The question, then, is whether the deconstruction of gender stereotypes, coupled with education against gender discrimination, can play a role in improving people’s mental health?

The answer, undoubtedly, is yes.

Bibliography

Ilaria Galizia

Ilaria Galizia completed a degree in Medicine and Surgery and specialised in General Adult Psychiatry. She also obtained a Master’s degree in Gender Studies and Politics, writing a dissertation about the impact of gender as a risk factor for depression. She has worked as a visiting researcher at the Psychological Medicine Department of King’s College London, collaborating with Cochrane Collaboration. As a clinician, she gained experience working at Mental Health Services in Italy. During her clinical activity, she has always maintained a gender and intersectional approach. Ilaria has a very keen interest in investigating the impact of gender on mental health. She is a member of the Global Health 50/50 where she is currently working on the GH5050 journal review.