This post is part of a series of weekly case studies addressing legislative approaches to rape in the EU. They are taken from a report written by our research associate, Nathalie Greenfield, which will be made fully available on our website (along with a complete bibliography of works cited) from June 17th 2019.

You can read the introduction to this case study here

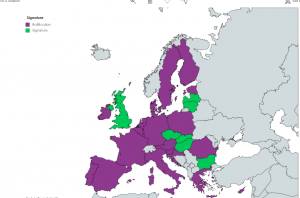

The third section of this report will comprise five case studies that explore existing rape legislation in five Member States: the UK, Sweden, France, Italy, and Poland. All five of these countries are signatories to the Istanbul Convention; only the UK has not ratified the Convention.

3.1: The UK

Three common law jurisdictions make up the UK: England and Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland. All three jurisdictions have clear legislation on sexual offences, and have passed legislation on consent that is clearly in line with an affirmative consent model. Three major Acts of Parliament outline the relevant legislation of each jurisdiction: the Sexual Offences Act 2003 for England and Wales,[1] the Sexual Offences (Scotland) Act 2009 for Scotland,[2] and the Sexual Offences (Northern Ireland) Order 2008 for Northern Ireland.[3]

Legislation on rape across the UK’s jurisdictions is compliant with international standards: rape is criminalised, it is framed as a depravation of bodily autonomy, and the definition of rape is grounded in consent. Consent must be affirmative.

3.1.1: England and Wales

Rape legislation

The Sexual Offences Act 2003 (SOA) is the primary legislation regarding VAW in England and Wales. Rape carries a maximum sentence of life imprisonment and is defined thus:

A person commits rape if “he intentionally penetrates the vagina, anus, or mouth of another person with his penis” and the victim “does not consent to the penetration” nor is there any reasonable belief of consent.[4]

This presents a change from previous law which was only concerned with vaginal penetration; now, both women and men may experience rape under the SOA. Notably, a person who commits the offence of rape must be male, as rape is defined with respect to penal penetration.

If penetration is by something other than a penis then the offence is an assault by penetration. A person commits assault by penetration when he “intentionally penetrates the vagina or anus of another person with a part of his body or anything else, the penetration is sexual, [the victim] does not consent to the penetration” and there is no reasonable belief of consent.[5] This offence is just as serious as rape as it still carries a maximum sentence of life imprisonment.[6]

Sexual assault is a separate offence, committed when a person “intentionally touches another person, the touching is sexual” and there is no consent or reasonable belief of consent.[7]

Consent

Consent is crucial to all three of these offences and is defined in the SOA. A person consents to an act “if he agrees by choice, and has the freedom and capacity to make that choice.”[8] The SOA lists situations in which consent is presumed to not be present, including if the complainant is asleep or unconscious, if the complainant is unable to communicate consent because of a physical disability, if the defendant has incapacitated the complainant through a substance, and if the defendant uses force or threats.[9] Further, caselaw in England and Wales has now established that consent can be rescinded at any time.[10]

Other criminalised sexual offences under the SOA include:

- Sexual activity with a child or in the presence of a child – §§ 9-10

- Abuses of positions of trust in connection with sexual activity – §§ 16-19 and 30-33

- Taking indecent photographs of children – § 45

- Trafficking – §§ 57-59

- Incest – § 64-65

- Exposure – § 66

- Voyeurism – § 67

Impact

Not only is affirmative consent defined in law in England and Wales, but new guidance for prosecutors was introduced in 2015 which stressed the importance of requiring defendants to explain how they obtained consent.[11] This guidance requires defendants to explain to police and prosecutors how they knew that the complainant was consenting, and that the consent was freely given in circumstances in which she was able to consent.

Despite the absence of a requirement of force, threat, or violence in the SOA’s definition of rape, the reality is that prosecution is unlikely to proceed in the absence of these elements.[12] This raises questions regarding implementation; defining progressive legal standards and enforcing them are separate inquiries, and point to the necessity of proper police and prosecutor training on sexual offences standards.[13]

With regards to victim support structures in England and Wales, several charitable organisations provide services for victims that meet the requirements of the Istanbul Convention. One of the main victim support organisations is the Rape Crisis network. Rape Crisis Centres across England and Wales provide services to victims, such as mental health care and legal support, and promote the needs of women and girls who have experienced sexual violence. Rape Crisis is supported by the government: it receives both government funds and private charitable donations.[14]

It must be noted that in spite of comparatively strong legislative grounding, many British women do not feel adequately supported by rape laws in England and Wales, or that the English legal system and its actors are equipped to manage sexual offences.[15] Rates of reporting, conviction, and attrition are discouraging, and legal protections tend to overlook and leave behind the most vulnerable women, such as immigrant women. As such, in March 2019 the UK government announced a full review into how rape and sexual violence cases are handled across the criminal justice system. The changes that this review will bring remain to be seen.[16]

3.1.2: Scotland

Rape legislation

The major piece of Scottish legislation regarding rape is the Sexual Offences (Scotland) 2009 Act, which defines rape thus:

A person commits rape if, with his penis, he “penetrates to any extent, either intending to do so or reckless as to whether there is penetration, the vagina, anus or mouth” of another without their consent and without reasonable belief of consent.[17]

Section 1 goes on to define penetration as “a continuing act from entry until withdrawal of the penis”, and specifies that both “penis” and “vagina” include surgically constructed anatomy. Again, rape must be committed by a male, but legally victims of rape can be both men and women. Rape carries a maximum sentence of life imprisonment.

Just as in England and Wales, penetration by an object constitutes the separate offence of sexual assault by penetration, and it still carries a maximum sentence of life imprisonment. Sexual assault by penetration is committed when a person “penetrates sexually to any extent, either intending to do so or reckless as to whether there is penetration, the vagina or anus” of another with “any part of [their] body or anything else,” without consent or a reasonable belief of consent.[18]

The offence of sexual assault makes it a crime for a person to do any of the following without consent or a reasonable belief of consent:

- Sexually penetrate the vagina, anus, or mouth.

- Sexually touch the victim.

- Engage in any other form of sexual activity which results in physical contact with the victim directly, though clothing, with a part of the body or an object.

- Ejaculate semen onto the victim or urinate on the victim sexually.[19]

The Sexual Offences (Scotland) Act also criminalises the following acts:

- Sexual coercion – § 4

- Communicating indecently – § 7

- Sexual abuse of trust involving children or mentally disabled persons[20]

- Administering a substance for sexual purposes – § 11

- Incest[21]

- Sexual exposure – § 8

- Voyeurism – § 9

Consent

Consent is defined as “free agreement.”[22] The Act explicitly provides that consent can be withdrawn at any time, that consent to conduct does not of itself imply consent to any other conduct,[23] and it lists circumstances where consent is presumed to be absent.[24] These include when a person is intoxicated to the point of being unable to consent, when a person is asleep, when violence or threats have been used, and when the only expression of consent is from a person other than the complainant.

Impact

Of the Act, the European Women’s Lobby says that it represents a positive change in how rape is defined in Scotland compared to previous legislation pre-2009, not least by including male rape for the first time.[25] However, only 24% of reported rapes reach court in Scotland, which the European Women’s Lobby argues is partly due to the major barrier of corroboration. Scottish law requires corroboration for all crimes, and the nature of rape makes it difficult to meet this requirement.[26]

Similarly to England and Wales, Rape Crisis is one of the primary networks for rape victims in seeking support in Scotland. Partly government-funded and partly supported by charitable donations, Rape Crisis Scotland provides essential services and support to victims of sexual assault.[27]

3.1.3: Northern Ireland

Rape legislation

In Northern Ireland, sexual offences are defined in the Sexual Offences (Northern Ireland) Order 2008. Rape carries a maximum sentence of life imprisonment. Just as in England and Wales, rape is defined thus:

A person commits the offence of rape if “he intentionally penetrates the vagina, anus, or mouth of another person with his penis” without the victim’s consent to penetration or a reasonable belief of consent.[28]

The offences of assault by penetration and sexual assault are also defined identically to how they appear in the SOA.[29] Northern Ireland takes an identical approach to consent to England and Wales.

The European Women’s Lobby argues that in spite of legislative protections, prosecution rates for rape in Northern Ireland “remain disgracefully low,”[30] illustrating the importance of going beyond legislation to address educational, social, and cultural factors in tackling VAW.

3.2: Sweden

Rape legislation

Moving on to civil law jurisdictions, Sweden’s penal code defines rape with respect to voluntary participation.

As of July 2018, a person commits rape under Swedish law when he “carries out sexual intercourse or some other sexual act that in view of the seriousness of the violation is comparable to sexual intercourse with a person who is not participating voluntarily”[31] (emphasis added). Rape carries a mandatory minimum sentence of two years, and a maximum of six years’ imprisonment.[32]

This definition of rape is incredibly current, and is one of the few consent-based definitions to be found in European civil law rape legislation.[33] Prior to July 2018, Chapter 6, § 1 of the Swedish penal code defined rape by the presence of violence or threat: “A person who by assault or otherwise by violence or by threat of a criminal act forces another person to have sexual intercourse […] shall be sentenced for rape.”[34] In removing the requirement of violence or threat by the perpetrator, Sweden proposed – in the words of the government – “the introduction of sexual consent legislation that is based on the obvious; sex must be voluntary.”[35]

Importantly, this new legislation also introduced the offences of ‘negligent rape’ and ‘negligent sexual abuse.’[36] These offences concern the intent of a person accused of rape, and occur when the perpetrator reasonably should be aware of the risk that the victim is not voluntarily participating but nevertheless engages in sexual activity. Negligent rape is punishable by a maximum of four years in prison. The introduction of this offence represents a welcome recognition of different situations in which consent is silent but not given; the test for negligent rape is whether a person could and did take all reasonable steps to determine whether consent was actually given. Adapting legislation to recognise liability for negligent is a new departure in rape law going beyond current international standards, responds to current debates about standards of proof for establishing consent, and sets a new high bar for other countries to follow.

Sweden’s penal code defines sexual assault other than rape thus: “A person who carries out a sexual act not referred to in Section 1 with a person who is not participating voluntarily is guilty of sexual abuse and is sentenced to imprisonment for at most two years.”[37]

Consent

Sweden’s new definition of rape is entirely consent based. Its language closely mirrors that of the Istanbul Convention and other international standards. The Swedish government summarises the core idea of the legislation thus: “Sex must be voluntary – if it is not, then it is illegal.”[38]

In assessing whether sexual participation is voluntary or not under the revised Swedish penal code, “particular consideration shall be given to whether the voluntariness was expressed through words or deed or in some other way.”[39] The penal code provides some examples of what is not considered voluntary participation. Notably, a person is never considered to be participating voluntarily if their participation is in response to violence or threats, the person is unconscious, asleep, bodily injured, in grave fear, intoxicated, or under the influence of drugs, or if the perpetrator “seriously abusing the person’s position of dependency on the perpetrator.”[40]

Certain attendant circumstances can reduce or augment the seriousness of a rape offence, which has an impact on the maximum sentence that can be served. For example, if the offence is considered gross (considering circumstances such as whether the perpetrator was physically violent, if there was more than one perpetrator, or if the victim was young), the perpetrator can be imprisoned for up to ten years. Consequently, the language of violence and threats has been retained in the revised penal code, but is now an attendant circumstance that can aggravate the crime of rape and not a required element.

Impact

In introducing a consent-based standard, the Swedish legislature responded to long-standing campaigns in Swedish civil society. According to the Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention, the first decade of the new millennium saw an increase in the number of reported sexual offences, which has been attributed to an increase in crime and a rising trend of reporting.[41] Accordingly, activist movements sought to pursue legislative change that could tackle the prevalence of rape in Sweden. The EWL already noted in 2013 that there was an active movement across lawyers, women’s organisations, and civil society to amend Swedish rape law according to the consent standard described in the Istanbul Convention.[42] In discussing the legislative change, the Swedish government sought to design its legislative modification to respond to the increasing incidence of sexual violence in Sweden and this civil society movement.[43]

To this end, as part of the 2018 legislation, the legislature tasked the Swedish Crime Victim Compensation and Support Authority with running information and education campaigns on sexual offences. These campaigns, which primarily target young people, seek to make all victims aware of their rights and to encourage them to report.[44] The Compensation and Support Authority was also tasked with producing an online training course and a teachers’ guide. Its activities are running for three years and are government funded. Engaging schools, producing information campaigns, and publicising rights under the new laws represent excellent practice. Not only do Sweden’s new laws recognise every person’s right to bodily autonomy and sexual freedom, but Sweden’s approach beyond the legislation itself respects and enforces the Istanbul Convention’s guidance on civil society engagement and victim support. Given how new the legislation is, it remains to be seen how it will be enforced.

3.3: France

Rape legislation

The primary legislation on rape in France is the French penal code. The rape of an adult is a crime, punishable by 15 years’ imprisonment. Rape is defined as “Any act of sexual penetration, of whatever nature, committed by violence, constraint, threat or surprise.”[45] This means that any one of violence, constraint, threat, or surprise must be present for a person to legally be raped. French law makes clear that it includes rape by a husband or civil partner in its definition.[46]

French penal law outlines attendant circumstances under which a sentence greater than 15 years’ imprisonment can be imposed. For example, rape committed on a vulnerable person is considered an aggravating circumstance to the crime, as is marital rape, gang rape, or incest, and all are punishable by 20 years’ imprisonment.[47]

Sexual assault is a secondary crime in France, and is defined as “any sexual infringement committed with violence, constraint, threat or surprise”[48] and is punishable by a 5 year sentence.[49]

Consent

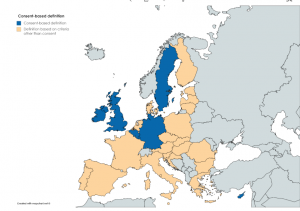

There is a notable absence of consent in France’s definition of rape. Legally defining rape based on the presence of violence, as opposed to the absence of affirmative consent, is not conform with the international standard outlined in Part One. This is especially noteworthy as France has ratified the Istanbul Convention, which outlines an affirmative consent model.

Impact

France’s definition of rape has resulted in some holdings that have shocked French and international communities, and which seem out of place in the post-#metoo era.

In 2017, the cour d’assises of Seine-et-Marne acquitted a 22-year-old man accused of raping a girl aged 11 because he did not meet the legal definition of rape. The girl’s family only learned of the rape when they discovered that she was pregnant. The man has since been convicted by the Paris cour d’assises and sentenced to a prison term of seven years.[50] Similarly, a court in the Val d’Oise reduced the charge of man accused of raping an 11 year-old-girl from rape to sexual assault, because the legal requirements for rape could not be met.[51]

These cases, which caused outrage and drew international media attention, raised many questions about the definition of rape in France and the lack of consent as the baseline standard where minors are concerned. France did not, and does not, have a minimum age of consent to sexual intercourse. Consequently, no matter the age of the victim, the requirements of penetration by violence, constraint, threat or surprise must be met. This is especially concerning when the government’s own Gender Equality Office notes that young women and children are the population most at risk from sexual assault and rape in France.[52]

Many civil society actors thus drew on these cases to advocate for the establishment of statutory rape with a minimum age of consent. President Emmanuel Macron’s minister for gender equality, Marlène Schiappa, proposed tackling this by explicitly removing the requirements of violence, constraint, threat or surprise for the penetration of a person under 15. After much controversy in summer 2018, the loi Schiappa, which would have established statutory ‘sexual assault with penetration’ in France, was not passed. Thus, although France retains the age of 15 as the threshold for statutory sexual assault (without penetration),[53] there is no statutory rape under the French penal code.[54] There has been no movement in the legislature to progress to a consent-based standard for the rape of an adult.

The European Women’s Lobby notes that many rape cases in France are not fully prosecuted because of prevalent stereotypes and ‘rape myths’ in the French judiciary.[55] Many rape cases are dismissed (sans suite) and others are sent to non-criminal courts where there are not judged as crimes but rather as sexual offences; consequently, many victims do not receive adequate compensation or have proper recourse to justice through the French legal system. Indeed, the number of rape convictions has dropped by 40% in the ten-year period from 2006 to 2017.[56]

With respect to social services and support, resources are scarce in France. Victims of rape and sexual assault rely on NGOs to provide services such as confidential telephone lines to give information and guidance to victims.[57] There is no national rape crisis service or support beyond NGOs, and legal support is limited. The European Women’s Lobby also argues that social services do not have the means to effectively help victims in France.[58]

3.4: Italy

Rape legislation

Italy is unusual in its legislative approach to rape in that it doesn’t define this crime separately from other forms of sexual assault. Article 609bis of the Italian Criminal Code states:

“Whoever, by force or by threat or abuse of authority, forces another person to commit or suffer sexual acts shall be punished with imprisonment from five to ten years.”[59]

Italy uses the term “sexual acts” to cover various forms of sexual violence. Further clarity on the elements of force, threat, or abuse of authority is provided in the legislation: Article 609bis condemns those who induce another person to commit or suffer sexual acts by abusing the conditions of physical or mental inferiority of the victim at the time of the act, or misleading the victim through hiding their identity.[60]

Outlined in Article 609ter, attendant circumstances to rape include:

- Using weapons or substances dangerous to a victim’s health (including alcohol),

- Deceiving a victim by feigning to be a public official exercising official duties, and

- Taking advantage of a victim’s physical or mental infirmity.[61]

Italy explicitly recognises statutory rape. Article 609 defines two forms of “violenza presunta”, where there is no requirement to show the elements of threat, force, or abuse of authority. Firstly, Italy recognises statutory rape when the victim is under the age of 14. Secondly, Italy finds statutory rape when a victim is under the age of 16 if the offender is the victim’s ascendant, parent (including adoptive parents), guardian, or any other person into whose care the victim has been entrusted.[62]

Italy also explicitly recognises the crime of ‘group sexual assault’. When more than one person participates in acts of sexual violence as defined under Article 609bis, each perpetrator is to be sentenced to six to twelve years’ imprisonment.[63]

Notably, in February 1996, sexual violence ceased to be a “crime against public morality and decency” and was fully recognised as a “crime against the person”.[64] Feminist movements in Italy had been campaigning for such a change for over 20 years.[65] The move away from a crime of public morality towards one of bodily autonomy, as per the Istanbul Convention, represents an important step forward for Italian legislation.

Consent

The Italian definition of rape is not consent based, but requires a showing of force, threat, or abuse of authority. This does not conform with international standards on consent, much less with the Istanbul Convention’s guidance of affirmative consent.

With respect to statutory rape, Italy does make one consent-based exception to this strict liability provision: it has adopted a close-in-age exemption. This type of exemption, otherwise known as a ‘Romeo and Juliet law’, prevents the prosecution of underage couples who engage in consensual sex when both parties are close in age to each other, and one or both are below the age of consent.[66] This is designed to prevent the prosecution of underage consensual sex as statutory rape.

Impact

The lack of a legal definition specifically for rape in Italy is highly concerning. As noted in Part One of this paper, it is difficult to begin to address the prevalence of rape if the act itself cannot be defined separately to other related acts. A crime that is undefined cannot be prosecuted; notice of legality is one of the founding principles of criminal law.

Italy has seen many high-profile and controversial rape cases, and activists on this subject remain very vocal. One such case, which highlights the country’s complex and problematic relationship with sexual assault as a subject matter, concerns a court ruling which suggested that a woman cannot be raped if she is wearing tight jeans; the court reasoned that tight jeans could not be removed without the help of the wearer, thus suggesting a lack of force or threat.[67] Though much discussed in the public arena, Italy’s rape laws are yet to be modernised.

As regards victim protection, Italy’s 1996 reform to rape legislation included provisions to protect the privacy of a victim pursuing prosecution. Within these provisions, Italy criminalized the divulgence of personal details or images of a rape victim, making this offence punishable by three to six months’ imprisonment.[68] Further, the Italian Code of Criminal Procedure provides that victims may request their sexual assault trial be partially or completely closed to the public, though – with the exception of minors – there is no guarantee that such a request will be granted.[69]

In conformity with international standards, the prosecution is not permitted to question a victim on her sexuality or sexual history unless the prosecution can show that it is necessary for the reconstruction of the facts of the case.[70]

3.5: Poland

Rape legislation

Rape is an offence against public decency and sexual freedom in Poland and is punishable by a term of imprisonment between two and twelve years.[71] Poland’s definition of rape is similar to Italy’s in the standard it sets and the language used. Under Article 197 of the Polish Criminal Code, a person commits rape when “by force, illegal threat or deceit, [he] subjects another person to sexual intercourse.”[72]

Within this same Article, the Polish legislature notes some special circumstances which have a bearing on the sentences available for the court to impose:

- If the perpetrator makes another person submit to a sexual act or perform such an act, he can be imprisoned for a term between six months and eight years.

- In cases of group rape, rape of a minor (under 15 years of age), or incest or parental abuse, a perpetrator can be imprisoned for a minimum term of three years.

- If the perpetrator acts with particular cruelty, he can be imprisoned for a minimum term of five years.[73]

Poland thus provides for statutory rape, and the aggravating circumstances of gang rape, abuse of authority, and particular cruelty, though naturally the latter necessitates a moral judgment in the place of a legal rule.

Importantly, rape is not classed as a crime of deprivation of bodily autonomy in Poland. Rather, it is included in Chapter XXV of the Penal Code Offences against Sexual Liberty and Decency, and appears alongside such crimes as forced prostitution and adultery.[74]

Consent

Poland’s definition is another example of rape legislation that does not take consent as its basic standard. Poland requires a showing of force, illegal threat, or deceit to convict a person for rape. Further, EWL notes that often, Polish legislation is interpreted to raise expectations that a woman should use active resistance against a person attempting to rape her in order to make her a credible victim.[75]

Impact

Poland has a low number of reported rapes for its large population size. For example, in 2011 1,748 cases of rape were reported for a population of 38 million.[76] This is unlikely to suggest that rape rates in Poland are uncommonly low; according to the EU Fundamental Rights Agency (FRA), 10-19% of Polish women have experienced sexual and/or physical violence since the age of 15.[77] This low reporting level thus is more likely to point to issues inherent in the prosecution of rape and the perception of sexual violence in Poland. Exceedingly burdensome procedures, an inadequate system of compensation for victims, and the stigma associated with sexual assault could be alternative explanations for such low reporting figures.[78]

On the subject of victim compensation and protection, the EWL notes that in spite of its obligations under the Istanbul Convention, Poland has few victim support structures in place and no basic standards of training for police and prosecution in working with sexual assault cases.[79] In 2013, the Sejm (the Polish Parliament) passed provisions that were designed to protect victims from retraumatisation: a victim could henceforth be interrogated only once, in the presence of a psychologist, and the interview would be recorded.[80] Though centring the needs of the victim is an important step, Poland remains far from the standards outlined in the Istanbul Convention.

Poland includes rape in the chapter of its Criminal Code dealing with sexual liberty and decency, not the chapter on “Offences Against Life and Health.” The EWL posits that this may suggest rape is a violation of social and cultural norms in Poland, and not seen as a threat to women’s life and health.[81] Although Poland’s legislation links rape to “decency”, the relevant chapter also treats sexual liberty. The issue would seem to be more that Poland treats sexual liberty and decency as part of the same legislative family, and less that rape is included in this chapter. As made clear in the international instruments discussed in Part One supra, sexual liberty and autonomy should be disassociated from societal moral judgments. This is especially pertinent in Poland, where societal values remain heavily influenced by religious conservatism.[82]

[1] England and Wales, Sexual Offences Act 2003, <www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2003/42/contents>

[2] Scotland, Sexual Offences (Scotland) Act 2009, <www.legislation.gov.uk/asp/2009/9/contents>

[3] Northern Ireland, Sexual Offences (Northern Ireland) Order 2008, <www.legislation.gov.uk/nisi/2008/1769/contents>

[4] Sexual Offences Act 2003, § 1(1)

[5] Ibid., § 2(1)

[6] Ibid., § 2(4)

[7] Ibid., § 3(1)

[8] Ibid., § 74

[9] Ibid., § 75(2)

[10] R v. DPP and “A” [2013] EWHC 945 (Admin) <https://www.judiciary.uk/wp-content/uploads/JCO/Documents/Judgments/f-v-dpp-judgment.pdf>

[11] See Crown Prosecution Service, ‘What is consent?’ available at <www.cps.gov.uk/publications/equality/vaw/what_is_consent_v2.pdf>; Crown Prosecution Service, ‘Rape and Sexual Offences Legal Guidance’, available at <www.cps.gov.uk/legal/p_to_r/rape_and_sexual_offences/>

[12] MC v. Bulgaria, ¶141

[13] For an example of good practice in this domain, see Case Study 3.2: Sweden, infra.

[14] See Rape Crisis England and Wales <https://rapecrisis.org.uk/>

[15] See, for example, Lizzie Dearden, ‘Justice system in ‘crisis’ as only 8% of crimes prosecuted in England and Wales’, The Independent, (25 January 2019), available at <https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/crime/crime-statistics-uk-justice-prosecution-rates-rape-victims-disclosure-police-funding-a8747191.html?fbclid=IwAR2tkPLgNmIKG35Be4IlBVtPNvrHFA6llCkVoeTmPUZKYMzT_CyaNV20Pu4>; Alexandra Topping, ‘Rape prosecutions plummet despite rise in police reports’, The Guardian, (26 September 2018) <https://www.theguardian.com/law/2018/sep/26/rape-prosecutions-plummet-crown-prosecution-service-police>; and Loulla-Mae Eleftheriou-Smith, ‘Rape victims facing ‘humiliating questions about clothing and sexual history during trials, MP reveals’, The Independent, available at <https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/crime/rape-sexual-history-assault-cross-examine-trial-court-voices4victims-plaid-cymru-mp-liz-savile-a7570286.html> [accessed 05/03/2019]

[16] UK Home Office, ‘Government sets out key measures to tackle violence against women and girls’, (6 March 2019), available at <https://www.gov.uk/government/news/government-sets-out-key-measures-to-tackle-violence-against-women-and-girls>

[17] Sexual Offences (Scotland) Act, § 1

[18] Ibid., § 2

[19] Ibid., § 3

[20] Scottish Government, ‘Information and help after sexual assault’, (2016) <https://www.gov.scot/publications/information-help-rape-sexual-assault/pages/7/>

[21] Ibid.

[22] Sexual Offences (Scotland) Act, § 12

[23] Ibid., § 15

[24] See Ibid., §§ 13-14

[25] European Women’s Lobby, Barometer on Rape in Europe, National Analysis: UK, (Brussels: EWL, 2013), p.1

[26] Ibid.

[27] See Rape Crisis Scotland <https://www.rapecrisisscotland.org.uk/>

[28] Sexual Offences (Northern Ireland) Order, § 5

[29] See Ibid., § 6 and § 7 respectively.

[30] EWL, Barometer on Rape: UK, p.1

[31] Regeringskansliet, Ministry of Justice Sweden, Swedish Penal Code, Chapter 6 § 1, (unofficial translation), <https://www.government.se/4a95e7/contentassets/602a1b5a8d65426496402d99e19325d5/chapter-6-of-the-swedish-penal-code-unoffical-translation-20181005>

[32] Ibid.

[33] Other civil law countries with consent-based definitions include: Belgium, Cyprus, Germany, and Iceland.

[34] Regeringskansliet, Ministry of Justice Sweden, Swedish Penal Code, Chapter 6, § 1, (translated by Norman Bishop), <https://www.government.se/contentassets/5315d27076c942019828d6c36521696e/swedish-penal-code.pdf>, p.24

[35] Government Offices of Sweden, ‘Consent – the basic requirement of new sexual offence legislation’, (April 2018), available at <https://www.government.se/press-releases/2018/04/consent–the-basic-requirement-of-new-sexual-offence-legislation/>

[36] Swedish Penal Code, Chapter 6, § 1(a)

[37] Ibid. § 2

[38] Ibid.

[39] Ibid., § 1

[40] Ibid.

[41] European Women’s Lobby, Barometer on Rape in Europe, National Analysis: Sweden, (Brussels: EWL, 2013), p.1

[42] Ibid.

[43] Government Offices of Sweden

[44] Ibid.

[45] France, Code pénal, Art. 222-23, <https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/affichCodeArticle.do?idArticle=LEGIARTI000006417678&cidTexte=LEGITEXT000006070719> (translated by author).

[46] Service-public.fr, ‘Viol d’une personne majeure’, (19 décembre 2018), available at <https://www.service-public.fr/particuliers/vosdroits/F1526>

[47] France, Code pénal, Art. 222-24

[48] Code penal, Articles 222-22 and 222-27 (translated by author).

[49] France has three levels of unlawful activity which increase in severity and punishment: the least severe is a contravention, then a délit, then a crime. Rape is a crime and sexual assault is a délit.

[50] Martine Bréson, ‘Viol d’une enfant de 11 ans : l’homme d’abord acquitté aux assises condamné à sept ans de prison en appel’, France Bleu, (28 November 2018), available at <https://www.francebleu.fr/infos/faits-divers-justice/viol-d-une-enfant-de-11-ans-en-appel-sept-ans-de-prison-infliges-a-l-homme-qui-avait-d-abord-ete-1543389369>

[51] Marjorie Lenhardt, ‘Val d’Oise : un homme de 28 ans jugé pour une relation sexuelle avec une fillette de 11 ans’, Le Parisen, (12 February 2018), available at <http://www.leparisien.fr/val-d-oise-95/montmagny-relation-sexuelle-a-11-ans-le-consentement-au-coeur-du-proces-12-02-2018-7555485.php>

[52] Secrétaire d’Etat chargé de l’égalité entre les femmes et les hommes et de la lutte contre les discriminations, ‘Enquête virage : viols et agressions sexuelles en France – premiers résultats’, (November 2016), available at < https://www.egalite-femmes-hommes.gouv.fr/publications/droits-des-femmes/lutte-contre-les-violences/premiers-resultats-de-lenquete-virage-violences-et-rapports-de-genre/>

[53] Code pénal, Art. 227-26

[54] Critically, a lot of the controversy around this law surrounded the fact that the statutory ‘sexual assault with penetration’ of a person under 15 years of age was classified as a délit and not as a crime, thus undermining the severity of the act.

[55] European Women’s Lobby, Barometer on Rape in Europe, National Analysis: France, (Brussels: EWL, 2013), p.1

[56] Ministère de la Justice, ‘Bulletin d’information statistique, no 164’, (September 2018), available at <http://www.justice.gouv.fr/art_pix/stat_Infostat_164.pdf>

[57] See Collectif féministe contre le viol <https://cfcv.asso.fr/>

[58] EWL Barometer on Rape: France, p.1

[59] EIGE, ‘Legal Definitions in the EU’

[60] Ibid.

[61] European Women’s Lobby, Barometer on Rape in Europe, National Analysis: Italy, (Brussels: EWL, 2013), p.1

[62] Ibid.

[63] Ibid.

[64] Ibid.; EIGE ‘Legal Definitions in the EU’

[65] EWL, Barometer on Rape: Italy, p.1

[66] ‘Age of Consent in Italy’, available at <https://www.ageofconsent.net/world/italy>

[67] Alessandra Stanley, ‘Ruling on Tight Jeans and Rape Sets Off Anger in Italy’, New York Times, (16 February 1999), available at <https://www.nytimes.com/1999/02/16/world/ruling-on-tight-jeans-and-rape-sets-off-anger-in-italy.html> replace with IT language piece and/or ruling itself if possible?

[68] EWL, Barometer on Rape: Italy, p.1

[69] Ibid.

[70] Ibid.

[71] Poland, Criminal Code (Poland) 1997, Kodeks karny, Dz.U. 1997 Nr 88 poz. 553, Chapter XXV, <https://www.legislationline.org/documents/section/criminal-codes/country/10>

[72] EIGE

[73] EIGE, ‘Legal Definitions in the EU’

[74] European Women’s Lobby, Barometer on Rape in Europe, National Analysis: Poland, (Brussels: EWL, 2013), p.1

[75] Ibid.

[76] Ibid., p.2

[77] FRA, p.18. The FRA notes that this figure is likely to be a conservative estimate.

[78] For more on these issues, see EWL, Barometer on Rape: Poland, p.2 and GenPol, Can Education Stop Abuse? Comprehensive Sexuality Education Against Gender-Based Violence, (Cambridge: GenPol, 2018)

[79] EWL, Barometer on Rape: Poland, p.2

[80] Ibid.

[81] Ibid., p.1

[82] For more on this, see GenPol, Chapter 1.