This post is part of a series of weekly case studies addressing legislative approaches to rape in the EU. They are taken from a report written by our research associate, Nathalie Greenfield, which will be made fully available on our website (along with a complete bibliography of works cited) from June 17th 2019.

You can read the introduction to this case study here

Despite comprehensive international guidelines and binding legal instruments as outlined in Part One, many EU Member States’ legislation on VAW is lacking. Most Members States recognise the issue of VAW, and have national action plans against VAW, but what is classified as VAW is not always consistent with the international standards outlined supra. These differences result in different approaches to criminalising behaviour associated with VAW; what is a crime in one Member State is not necessarily so in another. For example, in 2015 marital rape had still not been criminalised in Bulgaria, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, and Slovakia.[1]

Broadly speaking, domestic physical violence and sexual violence (including rape) are the main forms of VAW punishable by law in Member States. Domestic psychological violence, sexual harassment, and FGM are generally punishable in different ways depending on the Member State.[2]

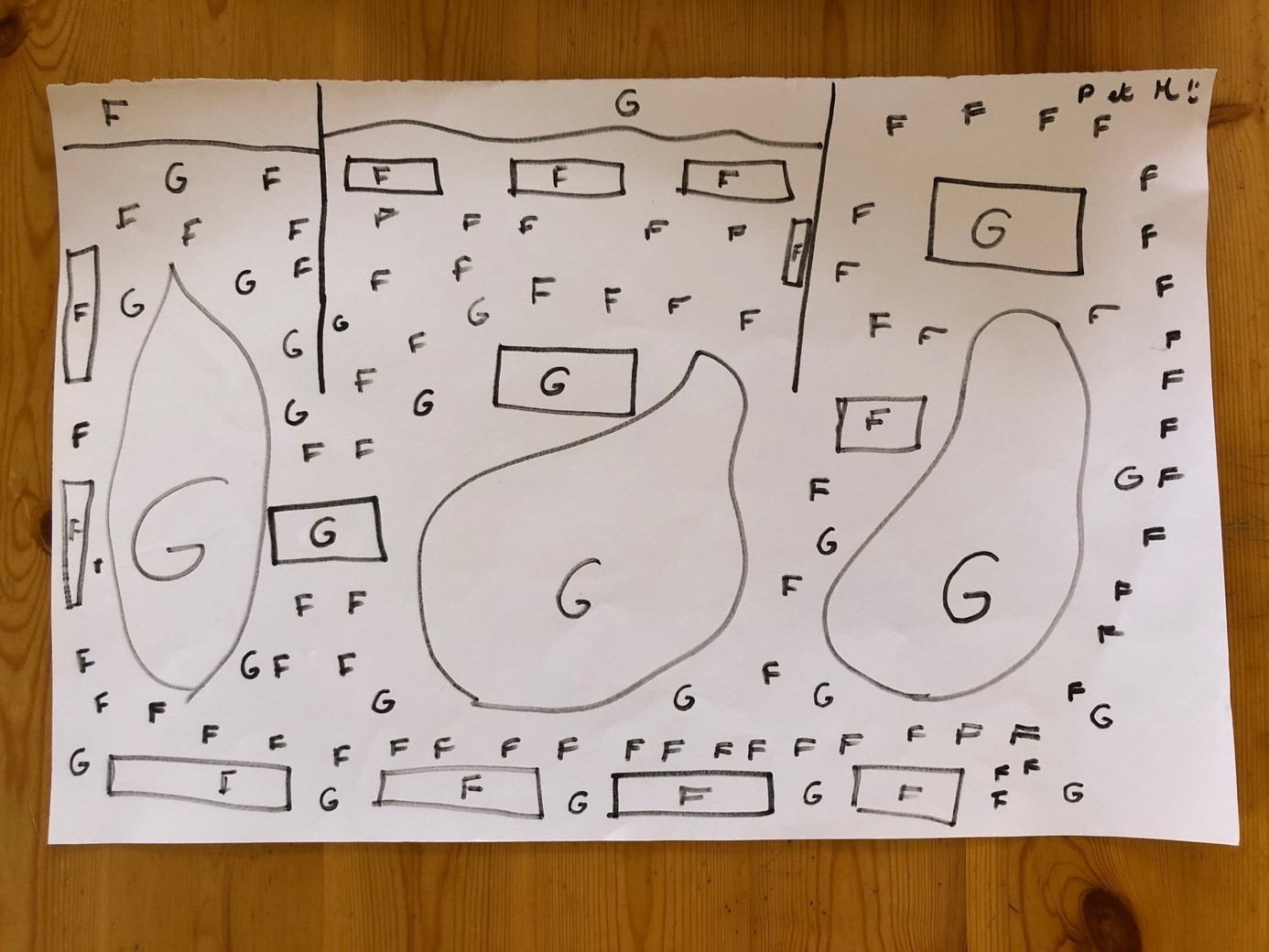

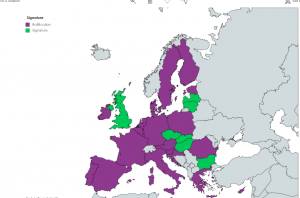

Not all EU Member States have ratified the Istanbul Convention. Of those that have, most have more to do to be entirely compliant with the Istanbul Convention’s rape provisions, as will be seen infra. The power of the Convention has not yet transformed into a strong, uniform legislative standard on rape across the European Union.

Figure 1: EU Member States that have ratified the Istanbul Convention

2.1: Rape legislation

Most Member States do not define rape based on a lack of consent, in spite of international agreement on a consent-based standard.[3] A detailed and comprehensive 2018 report from Amnesty International notes that the vast majority of EU countries have legal definitions of rape based on the exitance of certain circumstances – force, duress, and coercion.[4] Commonly, the use of force and coercion is used to distinguish between rape and lesser offences such as sexual assault or sexual intercourse without consent, meaning that an element of force is necessary in order for a crime to be prosecuted as a rape, as opposed to the defining element of rape being the absence of consent.

As will be seen in Part Three, many EU countries have laws which require the physical resistance of a victim in order to prove rape, a stance from which Germany, for example, has just removed itself: prior to November 2016, German legislation required a victim to have physically resisted in order to prove rape.[5] Attendant circumstances such as the victim’s age, disability, or the perpetrator’s relationship to the victim can also be factors in defining rape across Europe. To illustrate, in Finland, if a victim is aged between 16 and 18 and the perpetrator is in a position of authority over the victim (for example, as a schoolteacher) then Finnish law classes this situation as sexual abuse, and not as the harsher offence of rape. As a result, perpetrators in such situations get lesser sentences than perpetrators of rape.[6]

There are movements in some countries, especially in the wake of the #MeToo movement, to adopt consent-based definitions of rape. For example, recent high-profile rape cases in Spain involving multiple perpetrators are paving the way for Spanish legislation to recognise sex without consent as rape.[7]

Although the Istanbul Convention, ECtHR caselaw, and other international legal instruments require that rape and assault be defined as crimes against a person’s body and privacy, the sexual violence laws of several Member States are still framed in the language of honour and morality. In Malta, sexual offences fall under the chapter of “Crimes affecting the good order of families”; in Belgium and Luxembourg, rape is a “crime against the order of families and public morals”; in the Netherlands, rape is an offence against “public morals.”[8] Such language is worrying; framing rape in this way perpetuates harmful stereotypes about women’s bodily autonomy and sexuality.

2.2: Consent

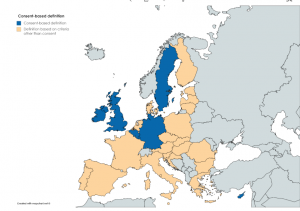

In all but seven of the 33 countries that have ratified the Istanbul Convention, the legal definition of rape is not in line with the Convention’s consent-based definition. Only Belgium, Cyprus, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, Luxembourg and Sweden define rape based on a lack of consent.[9] The role of activists and civil society will be instrumental in pressuring legislators to amend rape laws and definitions according to the Convention, as seen in Sweden: the legal definition of rape was changed to be consent-based in May 2018, after years of activism from women’s rights groups.[10] The three common law jurisdictions under the Convention (England and Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland) all have consent-based definitions of rape, but the UK is yet to ratify the Convention.

With respect to defining consent itself, Europe has a lot of work to do. Although international standards in the Convention and other bodies outline an affirmative consent model, Member States generally use other markers to establish a lack of consent.[11] Notably, the negative consent (‘no means no’) model is still predominant.

The difference between affirmative consent and the ‘no means no’ model is critical in establishing consent and thus defining the scope of crimes for which consent is required. The Istanbul Convention’s implementation mechanism, GREVIO, noted as much in their assessment of Austrian rape legislation: “there is […] a difference between sexual acts committed against the will of the victim (Austrian legislation), and non-consensual sexual acts (the Convention).”[12] One relies on negative consent, the other requires affirmative consent.

In outlining a negative consent model, many Member States still rely on the presence of force to establish a lack of consent, which necessitates victim resistance to show that force was used. This is incredibly harmful. As Amnesty International notes, “there should be no assumption in law or in practice that a victim gives her consent because she has not physically resisted the unwanted sexual conduct regardless of whether or not the perpetrator threatened to use or used physical violence.”[13]

Interestingly, the ECtHR suggests that even those countries that do not have a consent-based legal definition tend to give deference to the consent standard: “it is significant […] that in case-law and legal theory lack of consent, not force, is seen as the constituent element of the offence.”[14] This begs the question: why not adopt a uniform consent-based legal standard?

Figure 2: EU Member States that have a consent-based definition of rape

2.3: Victim support

Most Member States have some form of protective measures in place for victims of sexual violence and rape. Further, many Member States have specialist services and structures for victims, such as rape crisis centres, shelters, or refuges.[15] Such structures tend to be partly state-funded, and party dependent on donations.[16] In Northern Ireland, for example, victims can opt to be accompanied to the police station or to court by staff or volunteers of the country’s partially state-funded rape crisis centres, and staff often prepare complainants for court proceedings. The Nordic countries go even further: in Denmark, Finland, and Sweden, complainants have access to free counsel.[17]

Deterrents to reporting still need to be removed in many Member States. The UN’s CEDAW Committee notes that legal barriers to reporting crimes of sexual violence are an important factor in discouraging women from reporting, and lists examples of the various laws that act as deterrents to prevent women from seeking justice:

“All laws that prevent or deter women from reporting gender-based violence, such as guardianship laws that deprive women of legal capacity or restrict the ability of women with disabilities to testify in court, the practice of so-called “protective custody”, restrictive immigration laws that discourage women, including migrant domestic workers, from reporting such violence, and laws allowing for dual arrests in cases of domestic violence or for the prosecution of women when the perpetrator is acquitted […]”[18]

An example of good practice in removing such barriers can be found in Scotland: in April 2017, a Scottish legislative amendment introduced a duty on judges to provide the jury with instructions on rape myths and preconceptions in cases where there was a delay in reporting and when there was no physical resistance or force.[19]

Sources Cited

[1] European Parliament, ‘Parliamentary questions – rape within marriage’, (online question session, 2015) <http://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/P-8-2015-004211_EN.html?redirect> [accessed 08/01/2019]

[2] European Parliament DG EPRS, p.7

[3] See Part One supra; Amnesty International, pp.10-12

[4] Ibid., p.12

[5] Amnesty International, p.10

[6] Ibid., p.12

[7] Notably, the so-called La Manada case in Pamplona caused many protests because the perpetrators were found guilty of the lesser offence of sexual abuse, and not the more serious offence of ‘sexual aggression’, because they did not meet the legal standard for sexual aggression. In Spanish law, sexual aggression requires violence or intimidation, which the court did not find was present in this case.

[8] Amnesty International, p.14

[9] Ibid., p.9

[10] See Part Three, § 3.2 infra.

[11] Amnesty International, p.10

[12] Group of Experts on Action against Violence Against Women and Domestic Violence (GREVIO), Baseline Evaluation Report Austria, (Strasbourg, Council of Europe, 2017) available at <http://www.rm.coe.int/grevio-report-austria-1st-evaluation/1680759619> ¶141

[13] Amnesty International, p.6

[14] M.C. v. Bulgaria, ¶159

[15] European Parliament DG IPOL, p.40

[16] Amnesty International, p.18

[17] Ibid., p.16

[18] CEDAW, General Recommendation No. 35 on gender-based violence against women, updating general recommendation No. 19, CEDAW/G/GC/35, ¶29(b)(iii)

[19] Amnesty International, p.16