cn: sexual assault, intimate partner violence, harassment, violence against women.

Over 61 million European women have experienced physical and/or sexual violence in their lifetimes. Violence against women (VAW) presents a serious violation of human rights that is horribly widespread across the EU. Article 3a of the Istanbul Convention defines VAW as “all acts of gender-based violence that result in or are likely to result in, physical, sexual, psychological or economic harm or suffering to women.” VAW takes many overlapping forms; sexual assault, female genital mutilation (FGM), forced marriage, intimate partner violence, and sexual harassment just some examples, and such forms of violence are primarily (re)inflicted on women by men in order to (re)establish male social, economic, and political power.

Recognising that VAW is a widespread and direct violation of the EU Charter of fundamental rights with respect to dignity and equality, the EU is starting to pursue more substantial research in this field. Understanding the nature and scope of VAW in Europe is essential to tackling it, and to reinforcing and supporting the life-changing work that women’s organisations have been undertaking for many years through governmental work. The true extent of male violence against women across Europe, however, remains foggy.

Current data paints a picture of extensive abuse in Europe: over a third of adult women experience some form of sexual and/or physical violence at least once in their lifetimes. Over one in five experience violence at the hands of their intimate partner, over one in twenty is raped at least once, and over one in ten girls experience sexual violence before the age of 15. Very sadly, however, these numbers remain conservative estimates; the reality of the scale of VAW in Europe is likely to be much broader than current data suggests. A recent study conducted by the EU Fundamental Rights Agency (FRA) found that only “one in three victims of partner violence and one in four victims of non-partner violence report their most serious incident to the police or some other service.” Data collection problems prohibit detailed comprehension of VAW in the EU.

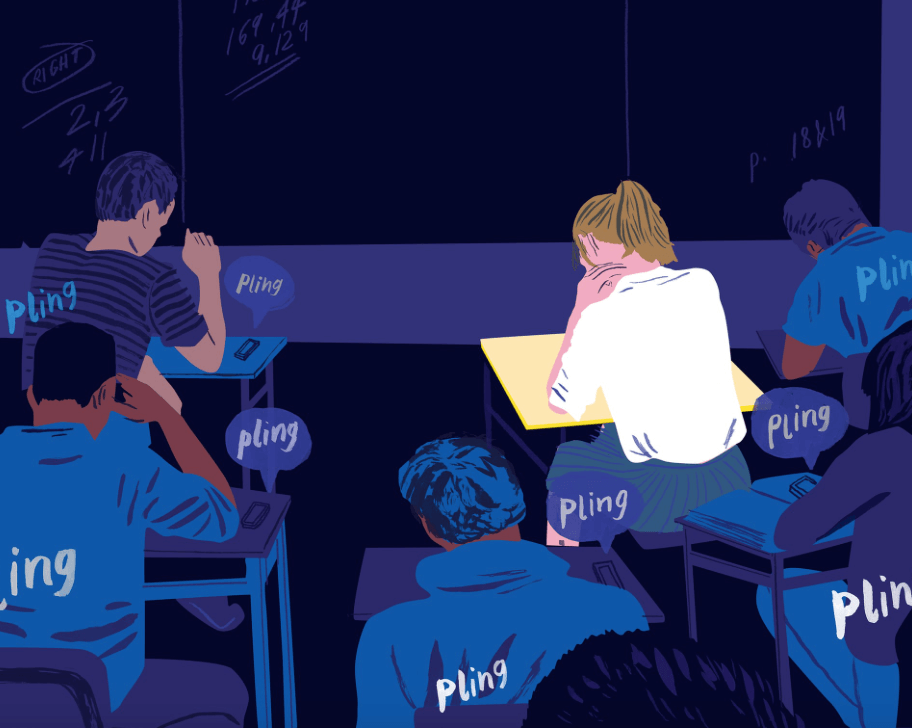

One of the most serious obstacles to the gathering of accurate data is systematic under-reporting of male violence. Fear of reporting, often compounded by a lack of trust in the police and judicial systems, contributes to this. The FRA recently found that one in four victims of sexual assault does not contact the police or any other organisation because of feelings of shame, embarrassment, or self-blame, and complementary to these findings, a recent report by the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE) linked low confidence in the police to low levels of reporting of gender-based violence. As an example, studies in Finland indicate a higher than average trust in the police (94% of the population trust the police in Finland compared to 70% across the EU), and higher than average reporting of sexual harassment (71% of women have reported experiencing sexual harassment, compared to 55% across the EU). Evidently, a large proportion of women who experience VAW do not speak of their experiences, and do not come into contact with national justice systems or social services; the crimes committed against them go unrecorded and ignored.

Perhaps most importantly though, recognising physical or sexual violence as violence remains a barrier to reporting. Legal definitions of violence contribute to what is societally categorised as violence, as is the case with marital rape, which is not criminalised in all EU Member States(1), or sexual harassment, which is not always legislated on. Consequently, instances of such violence often go unreported and overlooked. Even where violence is legislatively understood as such, though, cultural, religious, and societal norms can still prevent it from being recognised as criminal, and therefore in need of reporting. Patriarchal ideas in the individual and societal consciousness about the place of men and women, and their respective rights and freedoms, can influence what is considered normal behaviour, particularly in domestic relationships; these attitudes can have a vital impact on recognising, and thus reporting, violence.

Socio-cultural factors can also influence whether reporting violence is considered appropriate, or even possible. Cultural taboos can prohibit speaking about experiences of violence with authority figures, or even friends and family, especially in the case of intimate-partner violence. For a variety of reasons, women may not feel comfortable or safe disclosing violence. As noted by the non-profit network Women Against Violence Europe (WAVE), “the unequal power relationship between men and women, which is the root cause of violence, is also a barrier for reporting.”

So what are the implications of these obstacles to the collection of data on VAW? The above-mentioned interlinked factors that contribute to systematic under-reporting lead many studies into VAW to fall short of capturing the true extent of the problem. A nuanced top-down approach is needed to complement and reinforce the ground work that is being done by organisations and individuals across the EU, and policy is informed by data. Knowing the scope of violence against women therefore appears an obvious, though complex, element in tackling such violence; if we do not understand the nature of women’s realities then how can national and international organisations work for long-lasting and significant change?

NGOs working to provide services for victims of VAW offer hope for more accurate and comprehensive data collection, but their scope is often regional in focus and the information they provide varies as a result. Filling the informational void on the extent of VAW is an urgent task, and is a necessary part of a wider push in Europe to combat gender inequality at all echelons of society. Continuing efforts to address the range of economic, political and social power inequities felt by women (including rendering national systems fit for purpose) through both top-down and bottom-up approaches, are thus vital in encouraging women’s voices to be heard on their experiences of violence. Only then can we truly understand and address violence against women in Europe.

Nathalie Greenfield

Research Associate

(1) Bulgaria, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland and Slovakia are all yet to criminalise marital rape.