As a soon- to-be-graduate in European Legal Studies, I am fascinated by the legal vacuum that surrounds intersectionality. It goes beyond a gender binary, and therefore it seems like most Western jurisdictions do not recognise its existence. Yet, intersex people do exist, and there is an evident lack of research about intersexuality. Existing research doesn’t distinguish between Trans rights or intersex rights, which is a serious conceptual error. The legal and material needs of these communities are different and should be addressed independently. That is why I think it is so important to talk about intersexuality and address this legal gap by raising awareness.

What is intersexuality?

Intersexuality is an umbrella term that covers congenital conditions in which there is an atypical chromosomal, gonadal, or anatomical sex development. The most known cases concern hermaphrodites, who develop both male and female genitalia. More recently, medical research has discovered forty different variants of intersexuality.

While this condition can be apparent at birth, intersex traits can appear during puberty, or even in adulthood.

The frequency rate of intersexuality in the population is not certain. Data about intersex people lack, due to the stigma attached to this condition and the absence of long-term detailed studies. Nonetheless, according to the United Nations, between 0.05% and 1.7% of the population is born with intersex traits.

Why is it important to know about it?

Our legal traditions are historically based on the male-female dichotomy of the sexes, leaving little space for people who do not fit in this traditional binary system. Public toilets, marriages, and pension systems are just a few examples of cases in which being male or female could play a decisive role. This is also confirmed by the fact that this minority has been hidden for a long time. Recently, the legal gap between intersexuality and the male-female dichotomy can be bridged thanks to medical surgery.

Nowadays, the approach towards intersexuality largely reflects the theory of Professor John William Money. In the second half of the ‘900, the sexologist and psychologist developed a theory according to which the sex of a new-born is malleable. He theorised that it would be advisable to perform surgery on intersex children as soon as possible and raise them according to the sex assigned at birth.

No empirical medical research has backed his theory. Moreover, sex malleability overlooks the complexity of gender identity, which is not only about the anatomic sex appearance.

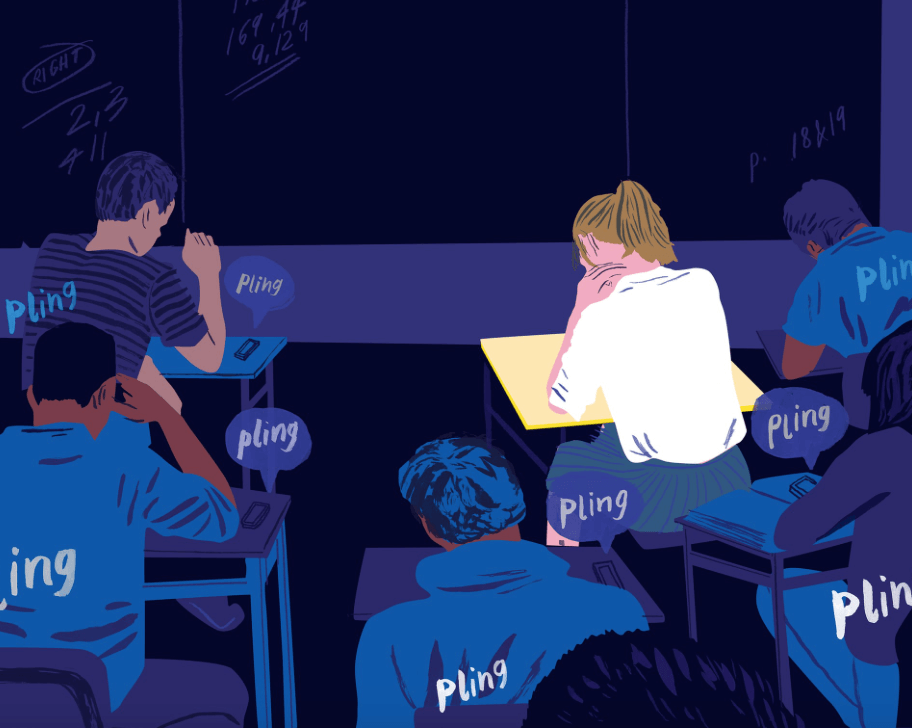

When an intersex child is born, the case is treated as an emergency. Even though sex is not clear, the sex assignment has priority in the treatment of the baby. In highly ambiguous cases, surgeries are carried out in order to confirm the baby into one of the two traditional sexes.

As the decision to perform surgery is taken by healthcare professionals and parents, the will of the intersex person is not considered. This approach may be understandable where the child’s life is at risk; however, the cases in which surgical operations are performed exceed those of life-threat. These medical procedures can often be highly invasive and they are frequently irreversible. They are usually accompanied hormone treatments, which should be lifelong and which may lead to hormonal imbalances.

As far as the paradoxical relationship between human rights and intersexuality is concerned, states seem to turn a blind eye. According to the comparative analysis “Trans and intersex equality rights in Europe”, published by the European network of legal experts in gender equality and non-discrimination of the European Commission, with the exception of Malta, the European member states do not explicitly protect intersex individuals in their legal systems. Maltese legislation pioneered the recognition of intersex rights. With a legal act, it prohibited non-necessary surgeries on non-binary individuals and it recognised the rights to bodily integrity and physical autonomy. Nonetheless, Malta remains the exception in the European scenario.

Few steps have been done on an international level. Recently, some international institutions have addressed the issue of intersex rights; among them, the High Commissioner for Human Rights of the Council of Europe, the Office of the High Commissioner of the United Nations and the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. Yet, states still seem reluctant to adopt concrete measures.

What can be done?

One of the most important things to do about intersexuality is to talk about it. Raising awareness about intersex people could bring them to feel more comfortable about their condition. Moreover, it would be useful to talk about this topic in public debate to put pressure on policymakers to implement for more inclusive and non-discriminatory laws.

Aesthetic surgeries on intersex children should be explicitly abolished by law; the more states abolish them, the more unlikely it becomes that individuals appeal to the neighbouring state to have medical operations be performed.

In order to address the legislative gap, some countries have adopted the third sex option. However, according to some scholars, this measure could increase, rather than reduce, intersex stigma. All these steps maybe not enough to ensure that the fundamental rights of intersex individuals are respected and promoted. We are in need of more, interdisciplinary research. Intersexuality has not been considered by academia for a long time. Many issues need to be further investigated; for instance, the outcome of early surgery must be analysed with long-term studies, the consequences of the third-sex option must be scrutinized and an appropriate collocation in the legal systems must be provided for intersex individuals.

Finally, we must reconsider what we regard as “normality” when it comes to gender identity and sex development. Indeed, sex should be considered as a spectrum rather than a two-option choice. This Copernican revolution would disrupt the world as it is known today, touching legal and societal systems, “but – as Fausto-Sterling put forward – in the long view – thought it could take generations to achieve – the prize might be a society in which sexuality is something to be celebrated for its subtleties and not something to be feared or ridiculed”.

Martina Molinari

University of Turin