At present, there are about 45 civil wars going on across the globe. 10 out of these 45-armed conflicts alone have resulted in over 1,000 fatalities. Whilst these figures might not be entirely surprising, we rarely stop to think about how violent conflict can act as an impediment to gender equality. Nor do we think about its impact on female labour force participation through fear, or the lack of public transportation usage due to neighbourhood distrust. The Sustainable Development Goal 5 have identified the need to ‘enhance women’s ability to participate in intra-household decision-making processes’ as one of the necessary factors needed to achieve gender equality by 2030. In order to do this, I suggest we need to look closer in to the impact of precarious living conditions on female decision-making power.

Gender equality begins at a micro-level of society: in the home. The ability to participate in intra-household decision-making empowers women by increasing their standing and significance within the family. It also provides them with a medium for expression in issues that affect their lives. Drawing on the example of the ongoing Mexican Drug War, I examine the ways in which such a socially distorted environment impacts home and day to day life, and how that can influence the relative decision-making power of a woman.

The Mexican Drug War began in December 2006 when the newly inaugurated President, Felipe Calderón initiated the fight against drug cartels. Since 2007, drug-related violence has escalated dramatically, claiming over 80,000 lives to date as a result of the aggressive clashes between the Mexican government and drug trafficking syndicates. According to a 2014/2015 national survey on victimization and perception of public security, more than half of the over 18 population considered insecurity and crime to be the most pressing issue at the state-level. The increasing number of homicides and other drug-related crimes has therefore undoubtedly hampered public safety, and the experience of women in both public and private space.

In my research, I draw on longitudinal data from the Mexican Family Life Survey (MxFLS) which interviewed more than 35,000 individuals in over 8,000 households across Mexico. Using information provided in the household decision-making questionnaires, I constructed a relative decision-making power index (defined as the absolute number of decisions a woman made in her household, minus the absolute number of decisions her husband made). A negative index consequently indicates lower bargaining power compared to her husband, and a positive index signifies higher relative decision-making power. To gain a more specific overview of the types of goods and services that couples bargain over within a household, I further divided decision-making questionnaires into four different categories: a woman’s private goods and services, her husband’s private goods and services, goods related to household expenditures and her children’s goods and services like health, education and food.

The results from my analyses revealed that the effect of homicides on a woman’s relative decision-making power was salient for only one particular type of good – expenditures on children’s goods and services. This finding is nonetheless unsurprising since women have been documented to have a greater preference in allocating larger income shares or resources to their children compared to men. Any negative shock to women’s incomes can be manifested by a decrease in their children’s expenditures considering the sensitivity of their bargaining power over this specific category of goods and services.

To provide additional insight into the possible mechanisms that govern the relationship between violence and a woman’s decision-making power, I also examined the impact of homicide rates on fear, neighborhood distrust, the modification of public transportation routes and the probability of employment. A case in point would be that a woman may limit her labor market participation due to the fear of being exposed to violent surroundings, or, she may have less social capital as a result of higher levels of distrust which could hinder employment prospects. Likewise, the dearth of security on public transportation routes compels women to commute on alternative paths to work that may take much longer, reducing the time they are able to dedicate to income-generating activities. Since income is typically used as measure for bargaining power, a reduction in wage earnings subsequently weakens the power a woman has to partake in intra-household decision-making processes.

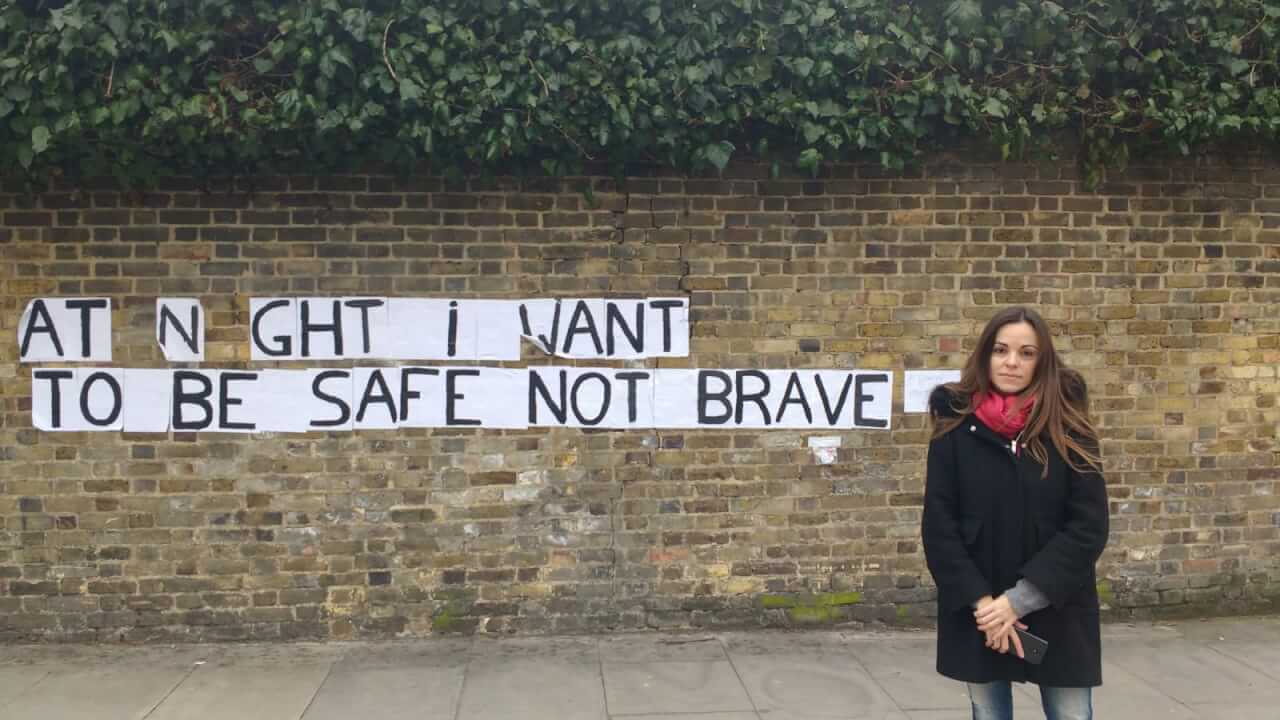

My study underscores the importance of providing women with greater protection during times of susceptibility in order to safeguard their autonomy in making independent decisions that impact them and their children’s well-being. It is imperative for policy-makers to consider the possible disproportionate effects of civil wars on women when formulating policies that strive to achieve greater gender equality. In Mexico City for example, women-only train carriages and buses are offered on metro lines, and the city of Puebla has also introduced ‘pink taxis’ operated by female taxi drivers that take on only female passengers. While efforts to implement systems that offer women greater protection cannot be discounted, more has to be done in streamlining and normalizing such gender-specific structures across the country as the provision of such services still remains woefully inadequate.

Audrey Au Yong Lyn

PhD Candidate

Department of Economics

University of Munich