TW: references to rape culture, victim blaming, and sexual violence.

Violence against women (VAW) is an issue that has plagued women from time immemorial. Its roots lie in ideas of subordination: the sense of women being male property in conventionally patriarchal societies. In recent years, VAW has gained renewed attention and has emerged as a hotbed of discussion around the world. Having worked with survivors of violence before, I began my Master’s with clarity on just one point: that I would write my dissertation on the topic of VAW. It is true that we live in a world where there is increased awareness of the issue. Many women support other women in opening up about violence, whilst social media movements like #MeToo and Time’s Up address sexual violence. However, the existence of a culture of victim-blaming, shaming and toxic masculinity continues to be a threat to women.

My dissertation, titled Aiding and abetting violence against women: a comparative analysis of Modi’s India and Trump’s America, focuses on sexual gender-based violence in India and the US. It explores how the Modi and the Trump regimes, as well as the factors that contribute to the ineffective redressal of and negative social attitudes towards VAW in India and the US, continue to exacerbate VAW in both countries. I chose to compare India and the US for three reasons. Firstly, I wanted to dispel the myth that VAW is a problem unique to the developing world, bound to ‘so-called’ backward cultures and traditions. Secondly, India and the USA are two of the world’s largest economies and yet, under their current political leadership, I believe that they are deteriorating socially. Finally, both the Modi and Trump governments lean towards the political right, and embolden far-right groups that are hostile towards minority groups, immigrants and modern feminism.

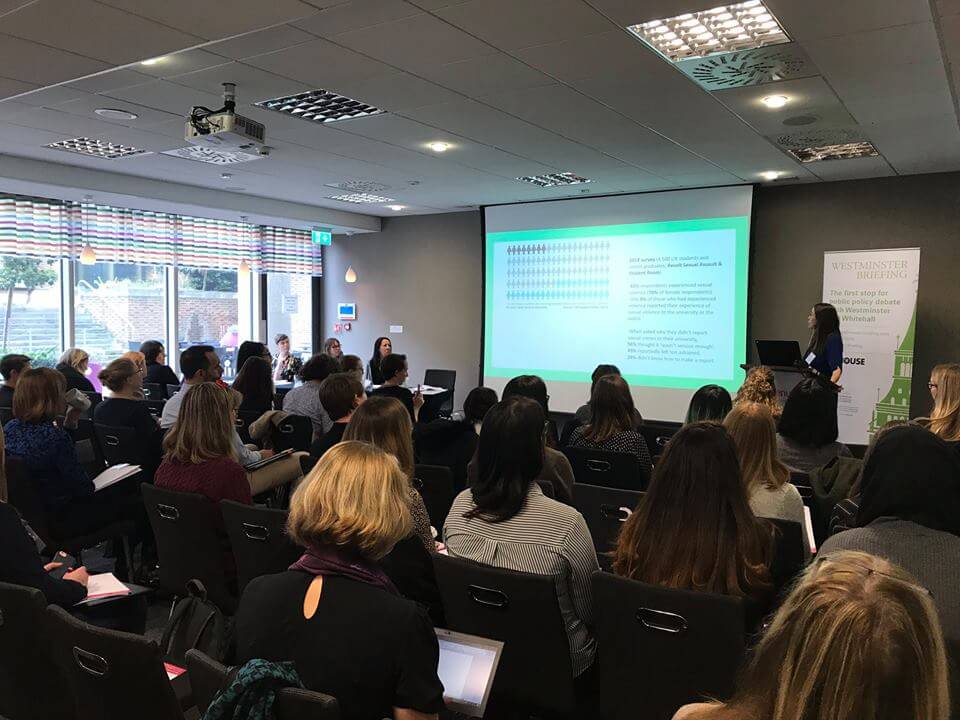

One of the most common forms of violence that is prevalent is both India and the US is sexual assault, especially rape. In fact, in a survey of global experts recently conducted by the Thomson Reuters Foundation regarding VAW, India was named the most dangerous country for sexual violence, while the US ranked third on this list. The US was also the only Western country on the list. Leading on from this, my first chapter dives into the astonishingly similar rape culture that is prevalent in both countries. Statistics from the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) in India and Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) in the US show that cases of rape and sexual assault are under-reported or unreported in both countries. This is not necessarily surprising considering that an integral feature of rape culture is the unwarranted focus on ‘what women did’ to invite sexual violence, rather than focusing on why men rape, and how it can be prevented. Even when victims work up the courage to report violence, their experience is minimised or silenced by insensitive police forces and victim-blaming. My chapter therefore argues that rape culture contributes to sexual assault as a form of social control over women, where they internalise the violence that they have a right to be protected against.

My work is also concerned with how toxic masculinity and nationalism emboldens the far-right, which then enables the creation of an environment that condones violence. It explains how both Modi and Trump used a combination of economic incentives and far-right support to win elections in their respective countries. Modi represents himself as a masculine “protector” of women and this language of masculinity along with Hindu right-wing politics leads to VAW and a restriction of women’s rights. For example, in the name of protecting women, violent moral policing has regained legitimacy to punish women for “erring”. Furthermore, Modi tends to maintain strategic silences when it comes to rape and VAW. The Modi government pursues an aggressive neoliberal agenda but a conservative social agenda in which women need protection more than rights or entitlements, eliminating the possibility of a rights-based discourse when it comes to VAW.

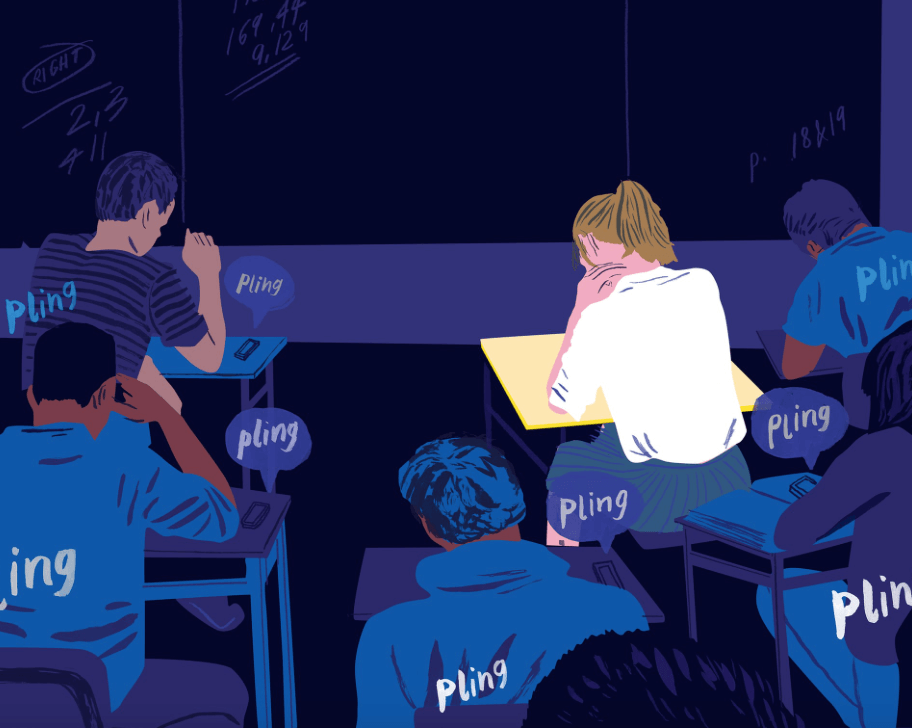

While Modi-masculinity is more subtle, Trump’s macho behaviour and unabashed sexism is the epitome of toxic masculinity. He faces around 17 cases of sexual assault and continues to flippantly dismiss or deny them all. His misogynistic comments and behaviour normalise sexual harassment of women and broadcast the message that women are inferior. As in India, this language of masculinity trivialises the issue of VAW. Through his actions such as cutting state funding to organisations like Planned Parenthood, Trump continues to demonstrate the point that he sees women’s issues as unimportant. When combined with the far-right ideology that resurfaced with Trump’s election, we are seeing an increasing shift towards the brushing off sexual assault as inconsequential or fabricated. Furthermore, this has created new platforms of violence, including entire far-right hate websites dedicated to bashing and threatening women.

This research has ultimately lead me to an uncomfortable awareness of the flawed redressal of VAW in both countries. These include a lack of state-support mechanisms, lack of sensitivity training of the police force and lack of institutional support in male-dominated environments. Whilst these findings paint a bleak global picture, I end this article (and my thesis) with a sense of hope in the push back against these two governments by the feminist movement. In a climate of structurally perpetrated VAW, we must turn to the feminist civil society groups and grassroots social organisations, as vital emblems of hope and resistance in the darkness.

Jushya Kumar

GenPol Research Intern