As part of our ongoing Covid-19 series, this week GenPol were lucky enough to interview Dr Nerea Irigoyen, a virologist from the University of Cambridge. In 2010, Nerea was appointed as a Sir Henry Wellcome Postdoctoral Fellow (Wellcome Trust), working under the supervision of Prof Ian Brierley, recording mechanisms in retrovirus and coronavirus. Since September 2018, she has been working as a Research Group Leader focusing on Zika Virus translation and its relationship with pathogenicity and disease.

We sat down to gauge her thoughts about the Covid-19 pandemic, and what she thinks you should know about it.

1) What’s life in your lab/department like these days? How are you holding up?

On Friday 20th March, all the labs in our Department were shut down. The University of Cambridge activated the red alert on Wednesday and gave us 48 hours to finish all the essential experiments. Since then, the whole lab has been working remotely!

2) What are you and your colleagues working on exactly?

In the lab we are working on the Zika virus. The Zika virus made the headlines in 2016 when it was linked to the sudden spike in babies born with significantly smaller heads, (what is also known as microcephaly) in Latin America. The virus, transmitted by mosquitoes and isolated in Africa in 1947, was never considered remarkable because previous cases had been asymptomatic. Therefore, our main interest in the lab is to know what sets the new American Zika virus apart from the African Zika virus and to know whether there are differences in how they replicate, produce their viral proteins and ultimately how they can cause disease.

3) At GenPol we have been looking at the gendered and intersectional implications of the pandemic. What are your thoughts on this?

The last two pandemics (Zika virus in 2016 and the current SARS-CoV-2) have had a huge effect on women. During the outbreak in Latin America, the Zika virus caused profound social impacts, particularly on women and girls. Despite recommendations from health authorities in endemic countries to postpone pregnancies for up to two years, it was made difficult for young women to avoid pregnancy due to a lack of clear reproductive health information by the Brazilian public health system. It was also difficult to access long-term contraceptives. In addition, abortion is criminalized in many Latin American countries and can be punishable with a 20-30 year prison sentence.

Women in Brazil also sought abortion through clandestine means, often involving dangerous methods such as caustic acid. In 2015, half a million women in Brazil underwent abortions, and tragically unsafe abortion was the fourth leading cause of maternal mortality. Furthermore, the lives of mothers with children diagnosed with Congenital Zika Syndrome have been profoundly impacted, with many women unable to maintain a job, whilst having to pay for medication and travel costs to access consultations in urban areas.

Associations that help victims of domestic violence have raised the alarm after Europe has become the epicentre of the coronavirus pandemic, warning that the stress caused by social isolation is exacerbating tensions and increasing the risk of domestic and sexual violence against women and children. In addition, fears for job security and financial difficulties are also increasing the likelihood of conflicts in homes with no previous history of domestic abuse. In this sense, the UK Home Secretary Priti Patel has indicated that refuges will remain open, and the police will provide support to all individuals who are being physically or emotionally abused. In addition, it is important to be aware that millions of children are spending more time online and that they may be even more vulnerable to online predators.

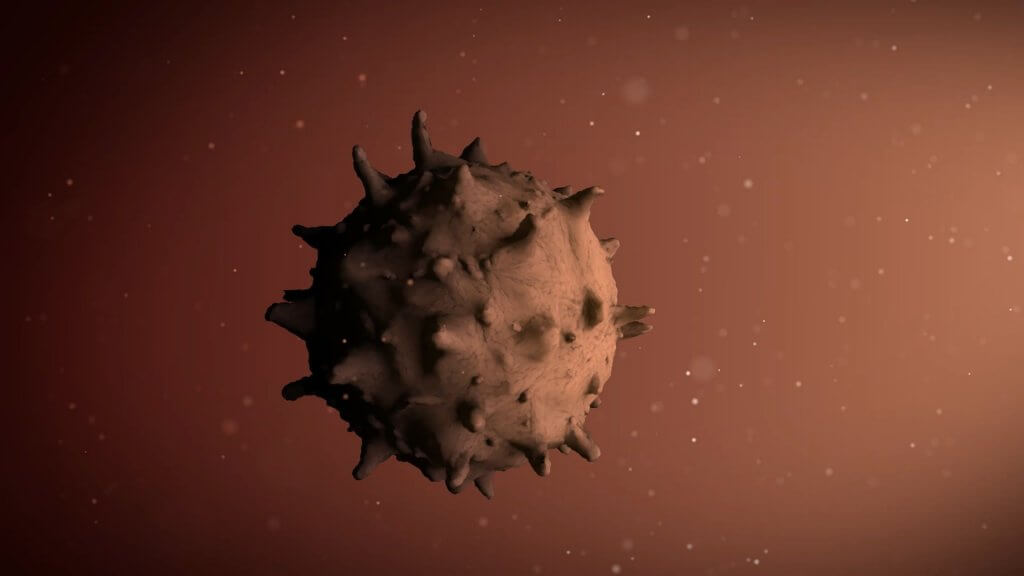

4) Why is SARS-CoV-2 so virulent? What makes it different from other viruses you have been studying?

This novel coronavirus, the SARS-CoV-2 is not so virulent compared to the ‘cousin’ virus SARS-CoV but more easily transmissible. The SARS-CoV outbreak in 2003 in China had a fatality rate of 10% but did not have the capacity to spread as easily as this.

SARS-CoV-2 has managed to spread across the globe in just a few weeks (it is important to notice that the first pneumonia cases in China were reported by late December) but although the fatality rate will be 1-2%, the great number of cases is hugely increasing the number of deaths.

The real dangers of this virus are that it is completely new for humans and not very well adapted yet. This is why it is so pathogenic. In addition, we do not have any immune memory to combat it yet. Also, viruses that are transmitted through respiratory droplets, produced when an infected person coughs or sneezes, are easily transmitted compared to other viruses such as mosquito-borne like Zika virus.

6) What is the likelihood of more different strains developing?

Unlike flu viruses, coronaviruses can proofread their genomes as they copy them, correcting mistakes along the way. This feature reduces their mutation rate and is probably the one bit of good news about coronaviruses. This makes coronaviruses less of a moving target for our immune system and our immunity will likely last for longer.

7) Is another recurrence (or second wave) of a a pandemic likely in your opinion?

Quite likely. In the near future there are two possible scenarios for the recurrence of this epidemic unless a vaccine is available. The first one will be during the release of the lockdown and this is why is extremely necessary to test all the population in order to prevent asymptomatic carriers to infect new people. The second scenario will take place next autumn, as good weather might lower the virus transmission in the Northern hemisphere but there is a high chance that it will come back later in the year. In the worst case scenario, SARS-CoV-2 will arrive at the same time as flu virus and this will cause health systems to collapse extremely quick. This is why we should start to prepare now for a potential second wave.

Currently there are a lot of research groups working on developing a vaccine against this novel coronavirus. We need to take into account that vaccines do normally take years until they can be developed. In this case, as we have done a lot of previous work with related coronavirus such as SARS and MERS, we will probably reduce this time but even though we will not probably have a safe and effective vaccine for the next 12-18 months.

8) What are the personal dangers faced by scientists who work with the virus? How do you protect yourselves?

Laboratory workers handling this virus should wear personal protective equipment (PPE) which includes disposable gloves, laboratory coat/gown, respirator (e.g. N-95), and eye protection. Furthermore, any procedure with the potential to generate fine-particulate aerosols (e.g. vortexing or sonication of specimens in an open tube) should be performed in a Class II Biological Safety Cabinet. After specimens are processed, work surfaces and equipment should be decontaminated and all disposable waste should be autoclaved.

9) Are there many women scientists in your lab? How are they coping with the extra load of work and work/life balance in these difficult times?

There are a big number of female scientists in the Division of Virology especially at a graduate and postdoctoral level, for most of us this is going to be the first time working from home, and for an uncertain amount of time. The idea of continuing with our full-time jobs while simultaneously homeschooling children, attending to elderly or sick relatives is extremely challenging. I think we need to acknowledge this new situation and that it will take time to adapt, probably more than expected. Probably everything will start to improve once as we settle into our new routines (i.e. designate a workspace or defined working hours). For the time being, we need to keep as positive as possible, this will help at getting the work done and at maintaining our mental wellbeing.

10.) What can we in our daily life do to help protect the most vulnerable?

The best strategy to help the most vulnerable during the current epidemic is to stay at home and practice social distancing. So far, this is the only way to avoid the spread of the virus and to flatten the epidemic curve.

Another way of helping vulnerable people is volunteering. That includes helping with shopping, delivering medicines from pharmacies, driving patients to appointments, bringing them home from hospital, and making regular phone calls to check on people isolating at home. Remember always to carry out this work in a sensible and vigilant way, always maintaining the physical distancing rules.