In 1993, the British Labour Party introduced a new concept: All Women Shortlists (AWS). For the then-upcoming 1997 election, only women would be presented as Labour’s parliamentary candidates in 50% of the Party’s target seats. A measure driven by Harriet Harman, the aim was to increase the proportion of women MPs. As a result, Labour’s 1997 landslide victory saw the number of women Members jump from 37 to 101. Such an increase simply would not have happened without the introduction of AWS.

Harman, in her 2017 book A Woman’s Work, argues that quotas are necessary for women’s progress in politics. She is absolutely correct. Indeed, the need for women’s quotas extends beyond politics to all areas in which women’s representation is far from equal to that of men: from the political chamber to the computer science lab, the professional sports field to the professional kitchen, the newspaper editing room to the cockpit.

Correcting the underrepresentation of women is not a given. It requires changing the status quo, which means challenging established mentalities and practices. Women make up 50.7% of the British population and 46.5% of the workforce, yet are far from constituting half of UK STEM employees (24%), FTSE 100 CEOs (28.0%), or, despite Harman’s best efforts, elected politicians (32.0%) Reflecting the gender pay gap, women are also more likely to live in poverty than men. Though we have made much progress in the workplace towards equality for men and women, the continued existence of pay disparity, gender leadership imbalance, and the absence of women-focussed HR policies in many workplaces shows that we still have far to go.

Ensuring that women are proportionately represented in all fields is widely regarded as instrumental to tackling social, economic, and political inequality. This is a cornerstone of feminism: women should be in a position to make decisions about their lives and the hugely varied issues that affect them. Implementing quotas for women in key areas in which they are underrepresented across a plethora of organisations is a simple yet effective way of achieving this goal.

The Council of Europe’s gender parity threshold lies at 40%. That is to say that if a company board constitutes 40% women then it can be said to be gender balanced. This being the case, why should we not implement quotas to ensure that women represent at least 40% of our political, economic, and social leaders, and at least 40% of employment categories in which they are greatly underrepresented?

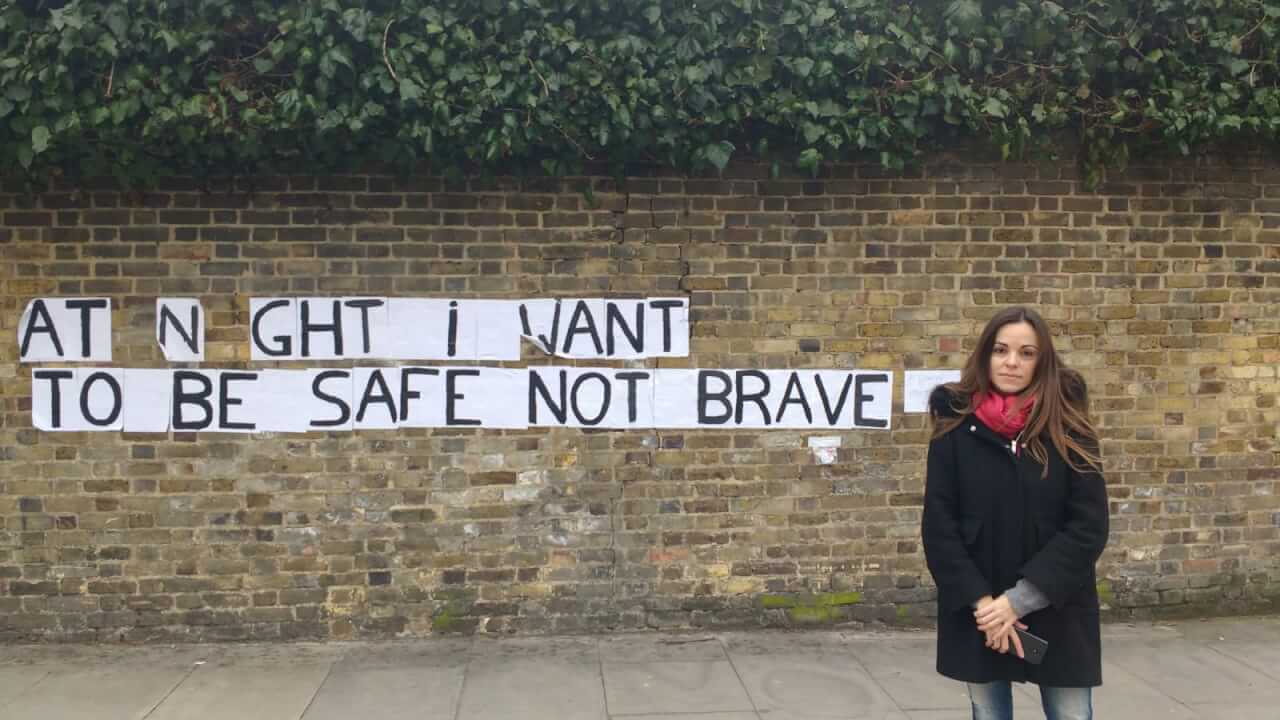

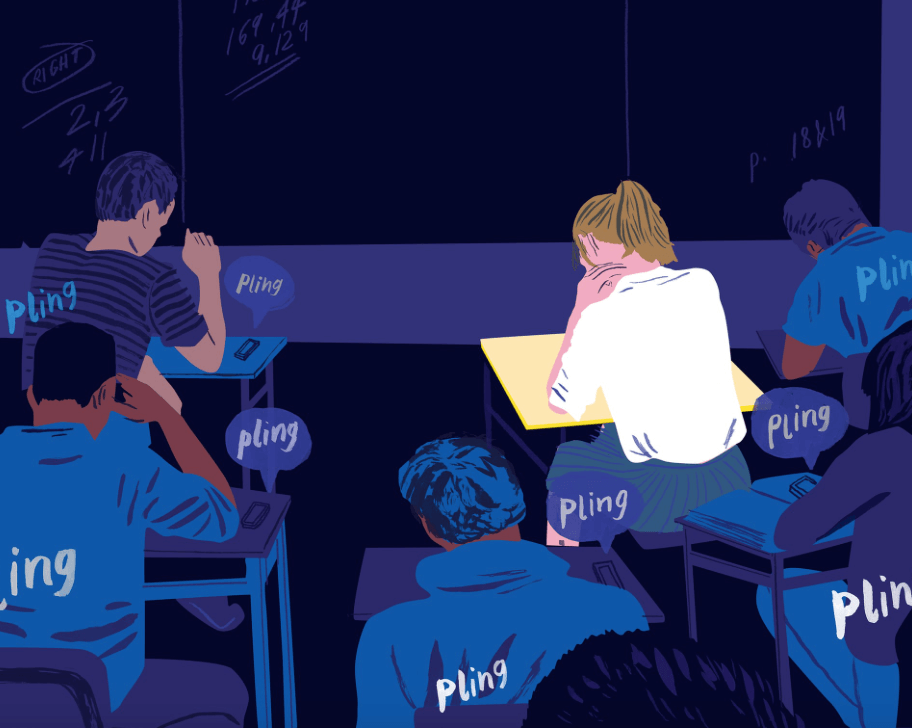

Harman states that without quotas, progress is too slow. The snail’s pace at which we are moving towards gender equality is proof enough of that. Targets and workplace policies only go so far before they stagnate and plateau. There is constant resistance to fostering female talent in many industries and women still struggle to shake the biases that have a detrimental impact on their careers. Quotas move us beyond the ‘sprinkle approach’, in which structural change is avoided and a sprinkle of difference in an otherwise homogenous group ticks the diversity box. We still live, and work, in societies designed by and for men. If we wait for the current chipping-away-at-the-patriarchy strategy to deliver equality, we’ll be waiting a long time.

Inspiration can be drawn from Northern Europe, as is common with many issues of gender and social equality. In 2006, the Norwegian government introduced legislation that required women to make up 40% of public and state-owned company boards. Iceland swiftly adopted similar quotas, and now women now hold 44% of corporate board seats. Much closer to home, we can see the success that AWS brought to women in the Labour Party, and to British women in general: women MPs were instrumental to the design and passing of the 2004 Domestic Violence Act and the 2010 Equality Act, to name but two examples. Implementing quotas in a variety of sectors would see women brought up and valued for their contributions to society, instead of waiting slowly and patiently for equality to dawn.

No, introducing quotas does not paint women as weak. No, quotas do not suggest that women need help in the workplace because they can’t get to the same positions as men. No, quotas do not constitute discrimination against men. Quotas simply acknowledge the structural issues in place that hold women back in employment and seek to redress them in a proactive and effective way. They acknowledge the importance of women’s proper representation, and correct institutional imbalances so that our workplaces reflect society, instead of a skewed version of it. Quotas strive to achieve what is naturally given in the gender make-up of all societies before patriarchal values interfere: equality. Carving out space for women to assume what should be naturally given would surely see tangible progress, as it has done in the instances where quotas have already been used.

Increasing women’s representation in order to pursue equality requires a firmer commitment and stronger action, but also for women to be in a position to assume equality across all areas of the workforce, including management. We need to have working conditions in place which facilitate equal access to opportunity, which sadly is not always the case. Limiting the talent pool for management recruitment in this way does a disservice to women and we all lose out. Thus, measures such as quotas that seek to increase women’s representation must be thought of in tandem with greater work-life balance and women-friendly policies, and must always be tackled in the context of addressing domestic inequality.

Nevertheless, actively creating space for women where they are underrepresented is important to protecting the rights and progress that so many before us fought to make a reality. As the election of the world’s number one delusional narcissist on the other side of the pond shows, these rights are fragile and require our ever-greater commitment. Of course, the idea is that one day such quotas and measures to institute equality will become redundant. But – to paraphrase one of my favourite Lord of the Rings moments – that day is not this day.

Nathalie Greenfield

Research Associate