This is the first of a two-part blog series by our Research Associate Venera Dimulescu, drawing on her first-hand research in to non-consensual pornography in Romania. In this first entry, she discusses the discourses and perceptions surrounding the rise of the ‘digital age’, and how we have failed to address the need for safety and security in our quest for progress.

****************************

During the two years I have spent researching non-consensual pornography in Romania, I’ve noticed that the problem in tackling online abuse is twofold: there’s a lack of accurate information about the digital world and an unsuitable choice of words in the construction of the narrative. When I started diving into the subject, I noticed there was a lack of information about how Romanians deal with online violence. There were no case studies, no statistics: only fast internet connections and increasingly cheaper smartphones and laptops. Everybody seemed to know something about the phenomena from the internet. But nobody estimated the impact of online violence, nor did they have the knowledge to combat it. As both a researcher and a journalist, I wanted to find a way, and ask how the language we use could help change these perspectives.

You might be wondering how we’ve ended up here? A few decades ago, the internet was perceived as a space of great opportunity: an alternative to the real world, a place where the right to freedom of expression would knock down the rule of prejudice and discrimination. In the first period of the technological revolution, offline/online and human/machine dichotomies were the new extensions of the old-fashioned mind/body thinking. Computers were designed as machines which would enable humans to experience this brave new world mentally and anonymously, away from their biological identities. The physical body was perceived as direct evidence of prejudice forced upon people by social norms: your neighbour’s gender, skin colour or physical strength help you recognize social status and hierarchy. The reality, in fact, was quite different.

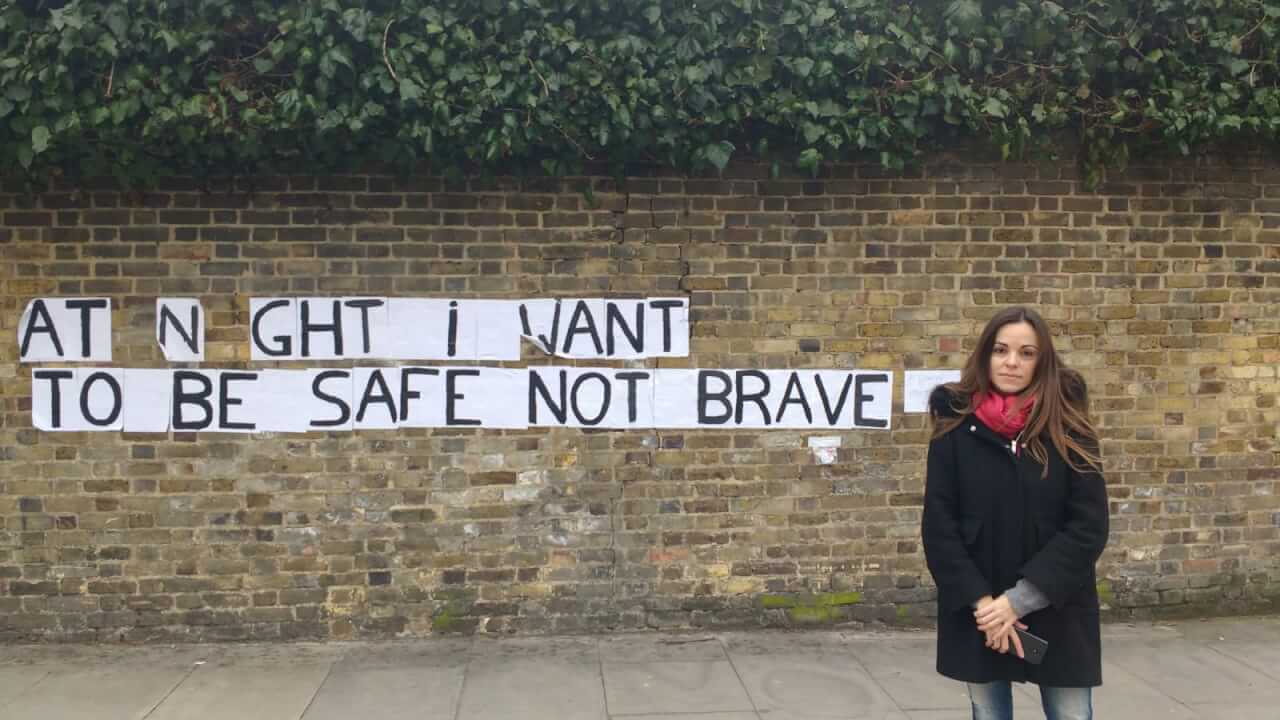

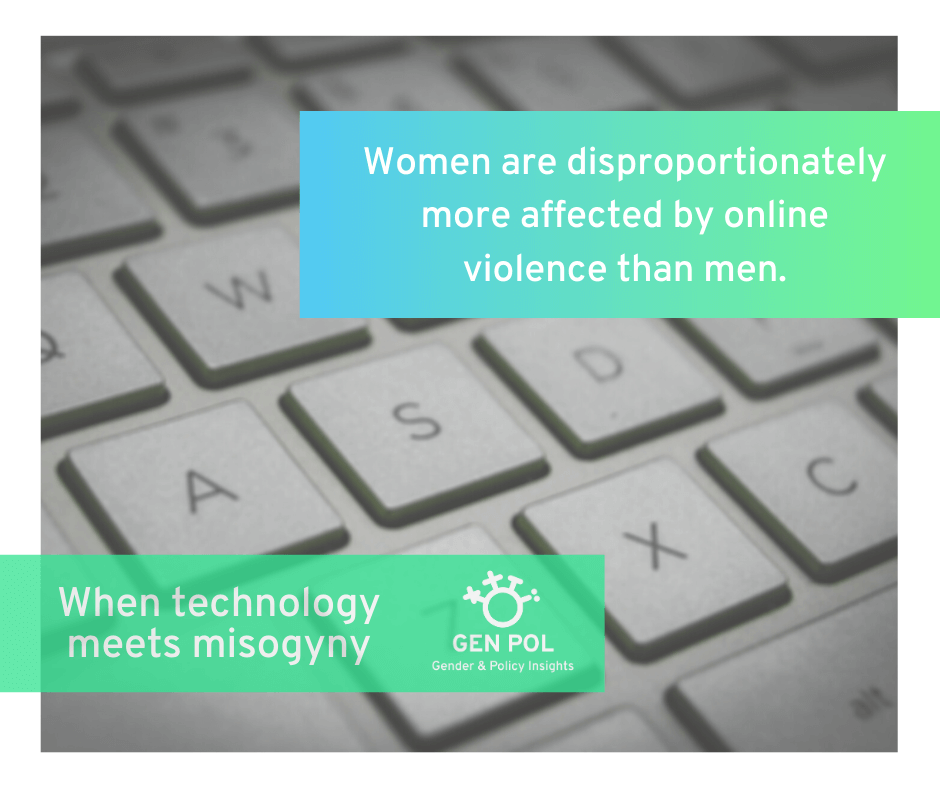

Despite its promise of an egalitarian future, online chat-rooms and public threads are hotbeds of violence against women. Anonymous hackers or trolls harass, frequently intimidate or steal personal information from women participating in the digital public sphere. One of the most widespread practice in online abuse is privacy invasion. Users often share intimate thoughts and images to strangers online, guarded by the comfort zone of their geographical distance, and many think their nudes are safe in their lovers’ private inbox. People often witness powerlessly how their personal lives are turned into public, accessible goods on the internet without their consent. In 2014, one in ten women living in the European Union were experiencing online abuse from the age of 15.

Over the course of the last decade, researchers have discovered that online abuse has direct impact on our lives. It leaves physical marks on the human brain, since psychological trauma is no different from physical trauma when it comes to our brain’s activity. However, information about the serious impact of online abuse on users’ mental health or legal protection often remains within the small academic communities. As GenPol’s policy paper highlighted, many European countries lack proper policies to combat and prevent online violence, although some have the legal tools.

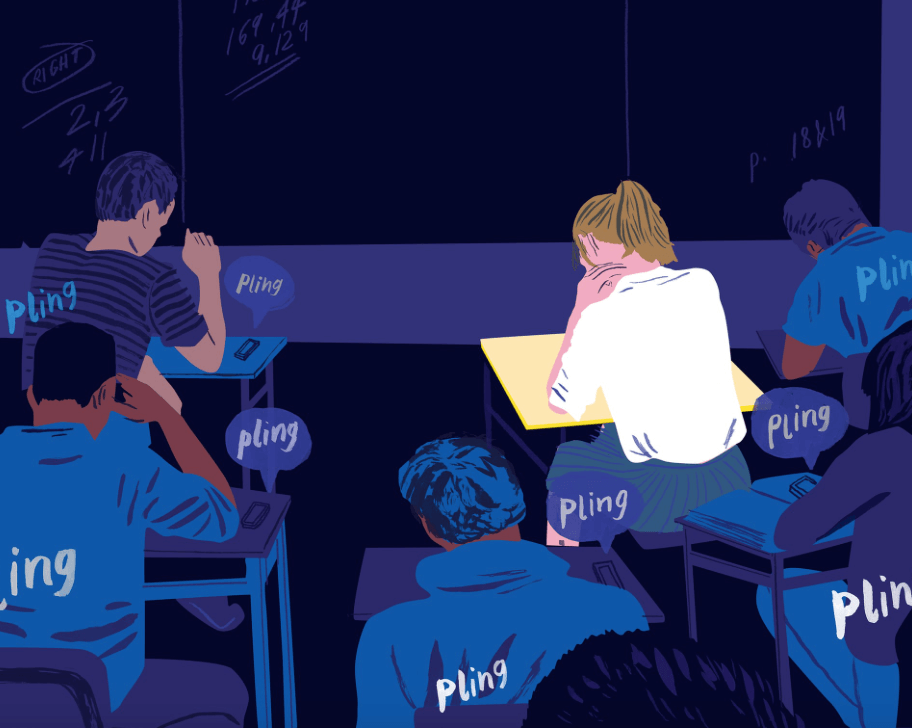

As Internet users, we can only expect an increase in online violence, as the internet has pierced through almost all of the EU households and has become a global village with worldwide access to information. A proper educational model is needed to help people understand online social phenomena and their impact.

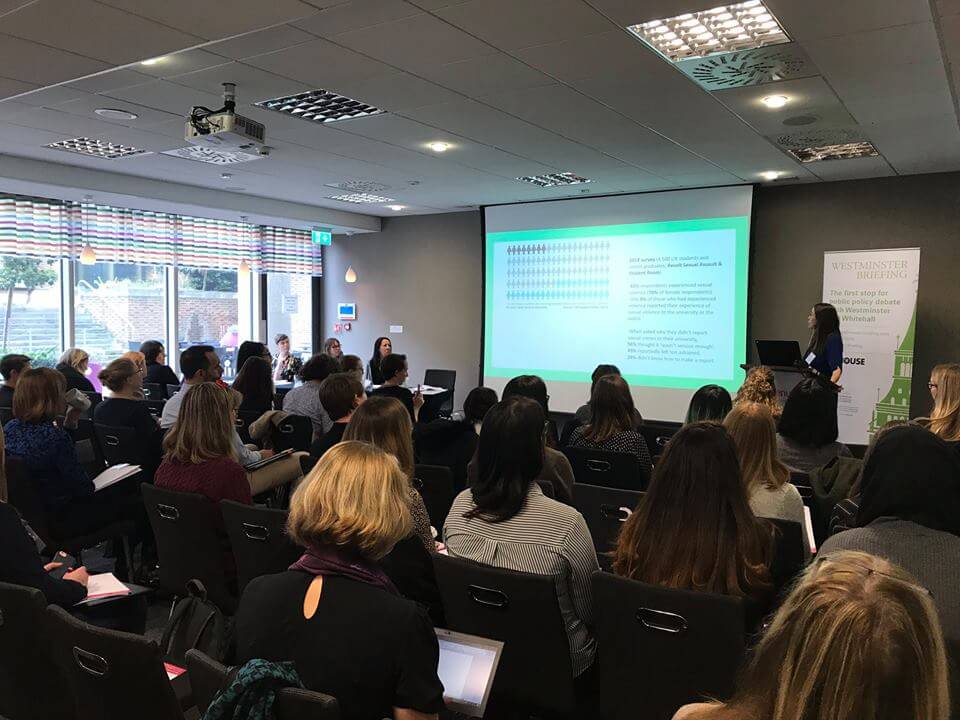

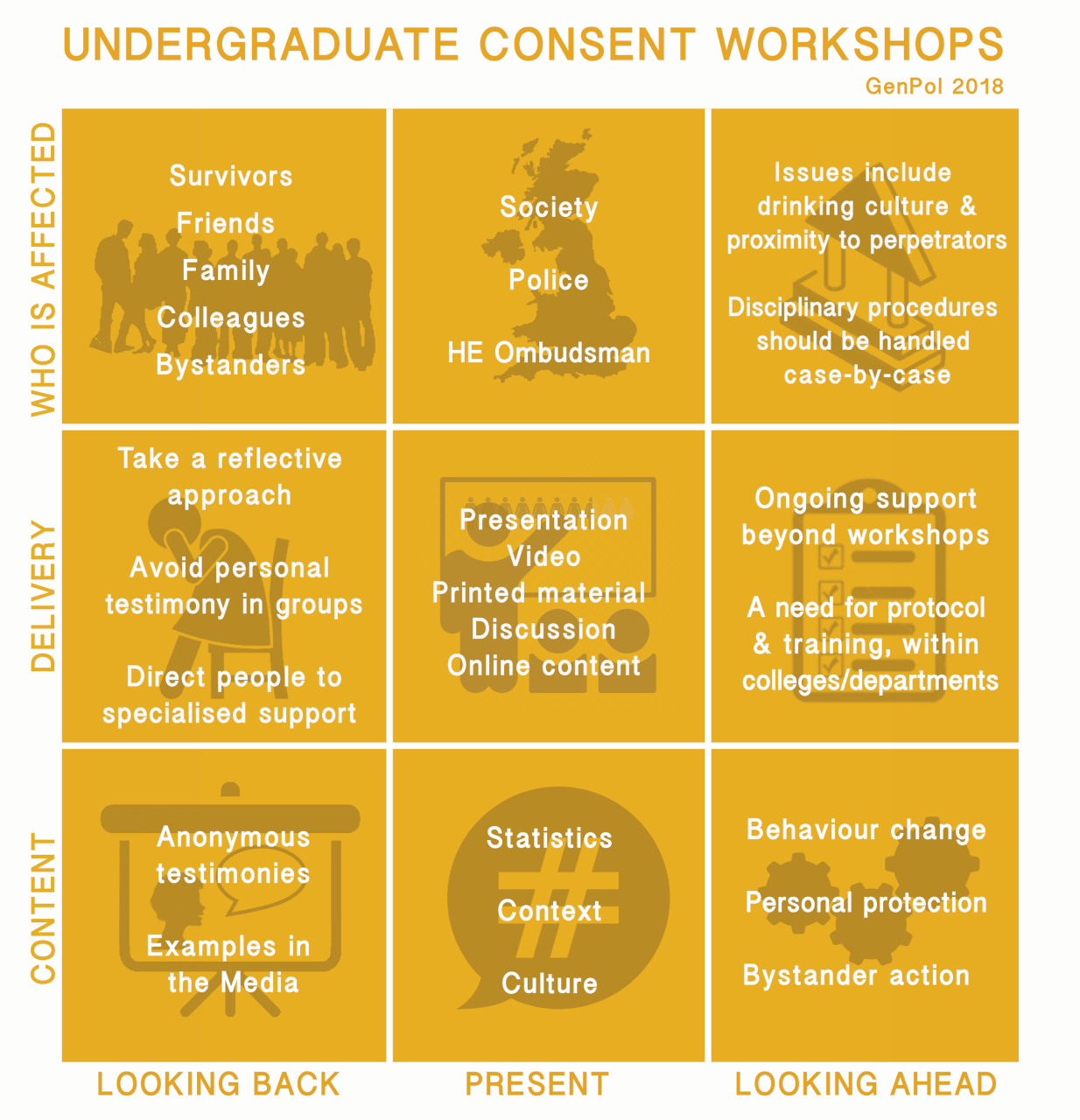

This should include teaching consent, privacy rights and legal protection online. But the first step in the process of understanding the digital world should be changing the narrative. It’s time academics used their privilege and built bridges in communication with teenagers, parents, teachers, politicians, authorities. By failing to address these gaps, we’re passively reinforcing epistemic injustice: victims won’t be equipped with the necessary vocabulary to describe their experience of abuse as we fail to explain the concepts to them with simple, accessible words.