What do sex education and The Great British Bake Off have in common? They can both make us cringe, they can both teach us new concepts, but, most importantly, they can both be axed in a moment by the powers that be, leaving us with something vital to our livelihoods missing.

Unlike the Bake Off, leaving young people without sex and relationships education (SRE) can have serious societal implications. To quote the International Planned Parenthood Federation, “comprehensive sexuality education seeks to equip young people with the knowledge, skills, attitudes and values they need to determine and enjoy their sexuality – physically and emotionally, individually and in relationships.” Comprehensive SRE, thus, recognises young people as sexual beings, gives them the opportunity to acquire essential life skills, and helps them to develop positive attitudes and values. Without classroom-based provision of such education, young people’s access to information on healthy relationships, pleasure, and sexuality can be warped or completely absent.

Reflecting its importance, SRE in some form is currently mandatory by law in 20 of the 28 EU Member States. Only Belgium, Cyprus, Italy, Lithuania, Poland, Portugal, Romania, and the UK do not count sex education among compulsory curriculum subjects (though the UK is in the process of making SRE a mandatory part of the national curriculum). However, mandatory inclusion of SRE in the curriculum is no guarantee of its quality, and the methods and actors involved account for a wide variation in sex education provision across the continent.

One of the most noticeable variations between Member States concerns the focus of SRE lessons. Most countries see sex education as an appropriate means of teaching young people about the biological elements of sex, and as a preventative measure to combat unwanted pregnancies and sexually transmitted infections. This preventative focus (sometimes called ‘negative’ sex education due to its concentration on the risks of sexual activity) forms the baseline for much SRE content. In most of the countries in which SRE is taught, the subject is time-tabled into biology lessons and taught by a biology teacher, which indicates that its primary aim is to cover physical and reproductive bases.

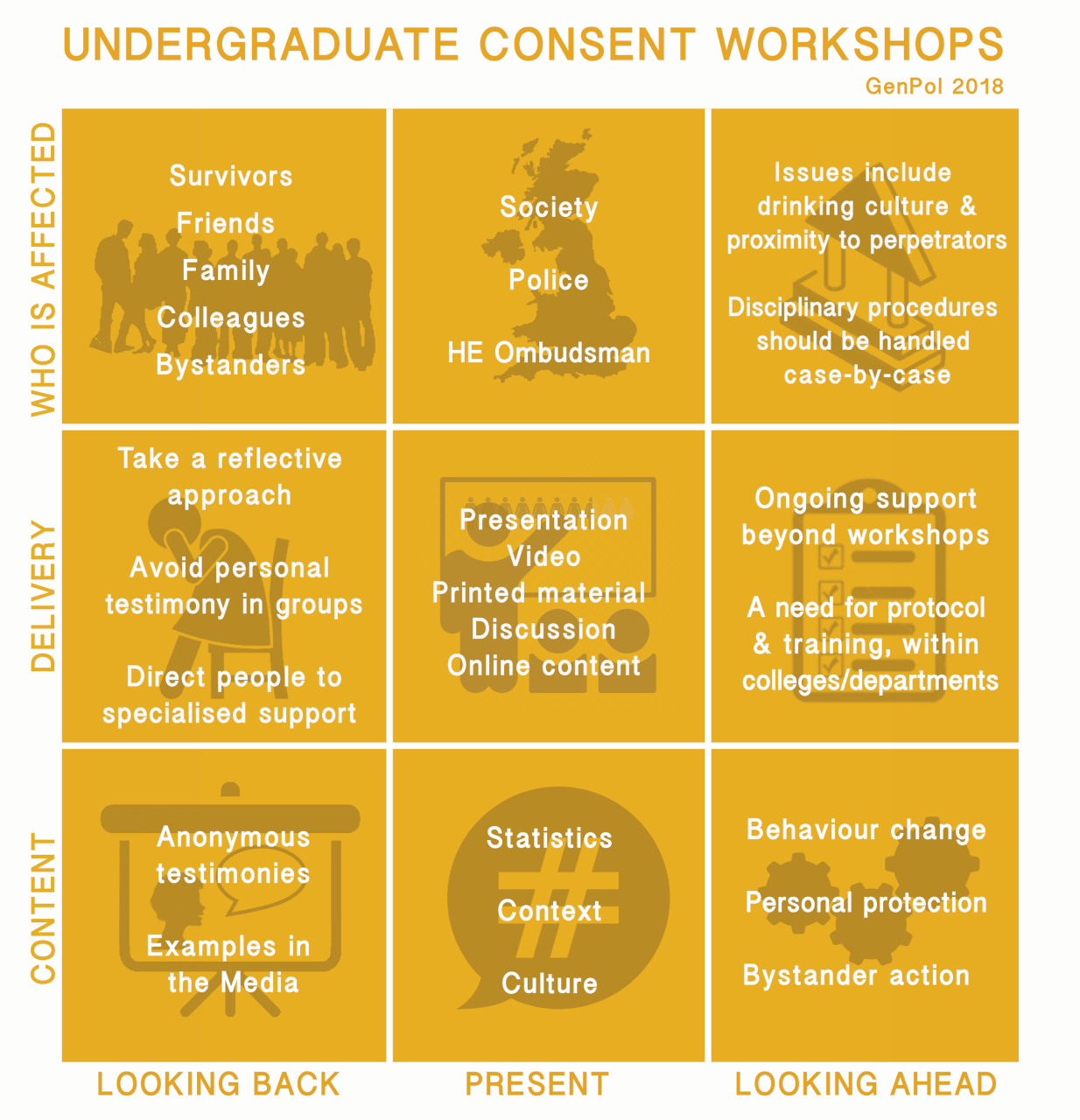

Some European countries have built on this biological focus to teach the relational and social aspects of sexuality. The Nordic and Benelux countries, in particular, promote this more comprehensive approach to SRE, going beyond a mechanistic coverage of biological facts to deal with the psychosocial aspects of sexuality. Where this is the case, as in Sweden for example, SRE tends to be taught as a separate curriculum subject and can involve the input of actors external to the education system (such as NGOs) in subject delivery. The involvement of NGOs in SRE provision often signals a more interactive approach to sex education and can include activities such as sexual health seminars (Sweden), sexual health campaigns (the UK) and counselling (Germany). Research has shown that whilst formal, teacher-led learning remains common, young people have a preference for a more interactive approach, and sex education has been proven to be more effective and more comprehensive when it establishes links with local sexual health services.

So why does the legal status, content, and delivery of SRE vary between different Member States? Firstly, the realities of sex education in financial, legal and pedagogical terms are shaped by the social and political views of individual countries, which diverge greatly. SRE provision can change as political actors and their priorities change, and the funds needed for training teachers, involving external actors, and investing in resources can fluctuate depending on the political leadership of individual Ministries of Education, as can the pedagogical aims of sex education. The government department in which SRE is housed often reflects a country’s approach to the topic: in the Czech Republic, SRE is coordinated by the Ministries of Education and of Youth and Sports, demonstrating an emphasis on youth development, and in Finland, the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health is involved, bringing the aforementioned psychosocial and components to the fore, along with emotional health.

Attitudes to sex and to young people’s sexuality are another important factor influencing SRE provision. Socially and religiously conservative countries, such as Hungary or Slovakia, tend to adopt a risk-emphasising negative approach, without providing much space in young people’s education for discussions surrounding sexual orientation, pleasure, or healthy intimacy. Indeed, SRE in Catholic Slovakia adopts a religious approach: the focus is on marriage and parenthood, and it can be taught by religious leaders as part of religious education. Comparing the terminology used to refer to SRE in different Member States interestingly betrays their difference in ideological focus and social attitude. For example, the recent campaigns in the UK to make ‘Sex and Relationships Education’ a mandatory part of the curriculum demonstrate a desire to go beyond biology and include relational components in the teaching of this subject, whereas the labelling of sex education as ‘Family Life Education’ in some post-Soviet countries, including Poland, reflects a focus on reproduction and social structure, and does not address sexual rights or pleasure.

Further, irrespective of whether or not SRE is mandatory, the quality and content of SRE in any given Member State is nationally inconsistent. Factors such as the location and type of school (urban or rural area; state or private sector), the teacher (experience and personal views), the local health services involved, and the support of parents and local actors, all have an impact on what children and young adults are taught about sex and relationships.

What is the effect of such disparity in SRE provision across the EU, then? Though difficult to quantify, there are clear links to be made between societal attitudes to gender discrimination, and non-comprehensive or non-existent SRE. The patriarchal power structures on which European societies are built are challenged by education which encourages young women to see themselves as equals to men in sex and in relationships, and which encourage young men and women to engage with emotional and relational issues. Attitudes to violence against women are a case in point: marital rape, for example, is not criminalised in either Hungary or Slovakia which have, as mentioned above, biological, risk-focussed SRE. If young people are not educated (in or out of the classroom) on what egalitarian, healthy relationships look like, then inequality, harassment and even violence become less easily recognisable as wrong.

Outsde of the classroom, young people turn to the mainstream media and the internet (where porn is easily accessible) to learn about sex and relationships. Given the patriarchal norms and harmful gender roles broadly perpetuated by these institutions, comprehensive SRE can be very helpful in providing a counter balance to their influences. Sex education programmes should be made mandatory in all countries, and should be broadened beyond a purely public health function, to be holistic in scope; the opportunities provided by relational and psychosocial SRE provision to tackle gender inequality on many levels are too great to ignore. Like the Bake Off, our access to comprehensive SRE might be out of our hands, but unlike GBBO it is far too important to social progression for us to try and live without.

Nathalie Greenfield

Research Associate