Students of social innovation know only too well the power of symbols and story-telling. Those who look for innovative solutions to complex, wicked social problems face, first, the challenge of conceptualising and clearly explaining to others the very social evils they are trying to address. This is usually no trivial matter: the way we consider approaching, say, violence against women and girls will very much depend on how, and through which lenses, we understand this phenomenon. Secondly, social innovators who are lucky enough to have identified viable solutions often struggle to illustrate this to donors, investors or policy-makers, and more generally to anyone who’s not as familiar with the subject as they are (or, indeed, as passionate).

There is, however, a third way in which the ability to forge narratives, and use sets of languages and symbols, is key to social innovation work. In fact, tackling some of the most entrenched social problems generally requires not only long-term, sustainable actions, but also a change in people’s habits and way of mind. This is where so-called cultural entrepreneurship, namely the processes and skills that allow innovators to (re)craft identities and symbolic practices to gain legitimacy and open up access to new resources and opportunities, often come into play.

Southern Italy, and especially my native Naples and Campania region, offer plenty of intriguing examples. Born in a land rich in traditions, rituals and unspoken rules, no Neapolitan would ever deny how much symbols and stories matter. It is no wonder that local social innovators pay close, conscious attention.

Take the case of Radio Siani, an anti-mafia social cooperative based in the small town of Ercolano (Naples), long-dominated by mafia interests, and once a central hub for extortion and drug trafficking. Radio Siani’s headquarters are in a flat that once belonged to a mafia boss. He used to watch the murders he had commissioned from the balcony .where young activists now enjoy their cigarettes. The flat currently hosts an anti-mafia web-radio (its origins lie in the fact that criminals in and out of prison exchanged messages through their own local radio). The organisation also runs educational activities for the local young people, and workshops for students who come to visit from all over the region. All visitors are asked to leave a message on the wall of what once was the boss’s kitchen.

Over the years, radio broadcasting has become increasingly intersectional, including a sex ed radio programme, regular coverage of LGBT+ issues, and awareness-raising emissions on the theme of disability. When interviewed, Radio Siani activists argued that mafia is fought not only talking crime and spreading ‘legality culture’, but also working towards an equal, democratic and non-violent world, where everyone’s rights, particularly those of the traditionally oppressed, are defended. It is definitely not by chance that the organisation was involved in the setting up of Lilith, the very first gender-based violence emergency point ever opened in Ercolano (now sadly shut down due to lack of funding).

This intersectional ethos is evident in Radio Siani’s effort to reclaim the mafia’s own words and symbols, and propose positive language, rituals and role models to those who were born in a mafia-dominated area. In fact, the radio and the social cooperative are both named after Giancarlo Siani, a Neapolitan journalist killed by the mafia in 1985, aged 26. The flat is packed with pictures and images of Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino, Sicilian judges also murdered by organised crime, and of Miriam Makeba, one of the most audible voices of the anti-Apartheid and civil rights movements.

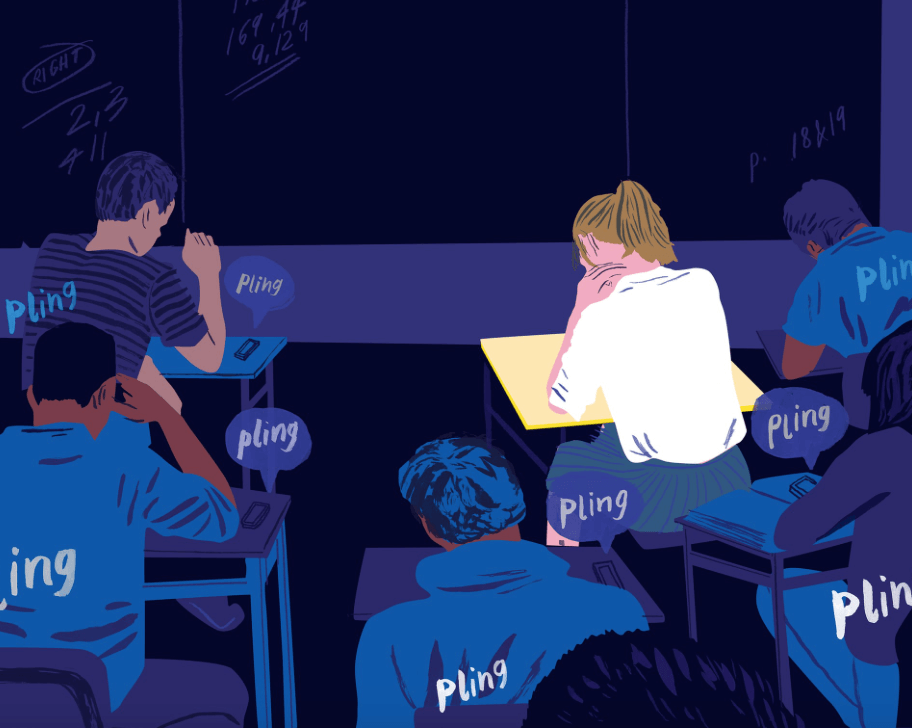

The cooperative’s members have recently started to engage in agricultural work, producing a special breed of tomatoes in a field which was, too, once confiscated from a criminal family. The tomatoes, small and pointy, have been nick-named pizzini, slang word for sharp-edged objects but also for the messages whereby the Sicilian mafia used to communicate. Agricultural projects also serve the purpose of offering work opportunities to kids just come out of juvenile prisons in the area, many of whom share a migrant background or a history of mental health issues. Radio Siani’s staff makes a point to provide them with professional and personal mentorship, as well as examples of healthy, non-violent masculine bonds.

Other actors in the Ercolano’s anti-mafia network are equally cultural entrepreneurship-conscious. The Associazione Anti-Racket, the charity which unites shop-owners and entrepreneurs who rebelled to mafia’s extortions and reported offences to the police, organises a yearly ‘anti-extortion’ walk, where the civil society is invited to take the streets and reclaim the right to own their town. Enlightened local school principals adopted an open-door policy, arguing that schools should be open well beyond class-time to offer kids a stimulating alternative to life on the street. The carabinieri (Italian military force with police duties), very much involved in anti-mafia work and central to the eradication of the extortion practice in Ercolano, are about to move to a new head-quarter, in the very centre of the town once controlled by criminal families.

Tomatoes and public walks, radio broad-casting and messages on the wall, then, all fulfil a similar purpose. They are the tools whereby activists and innovators reclaim bits and pieces of an oppressive system (that of organised crime, or, say, that stemming from the intersection of the discrimination directed against women, the LGBT+ community , migrants and disabled people), re-forging them for new purposes. They are meant to empower people and local communities in innovative ways, with the long-term purpose of making social change possible.

Stories worth telling? I’d say a couple of very poignant lessons to be learned.

(This blog is a revised version of a longer articles published on the Cambridge Judge Business School’s website).

Lilia Giugni

GenPol CEO