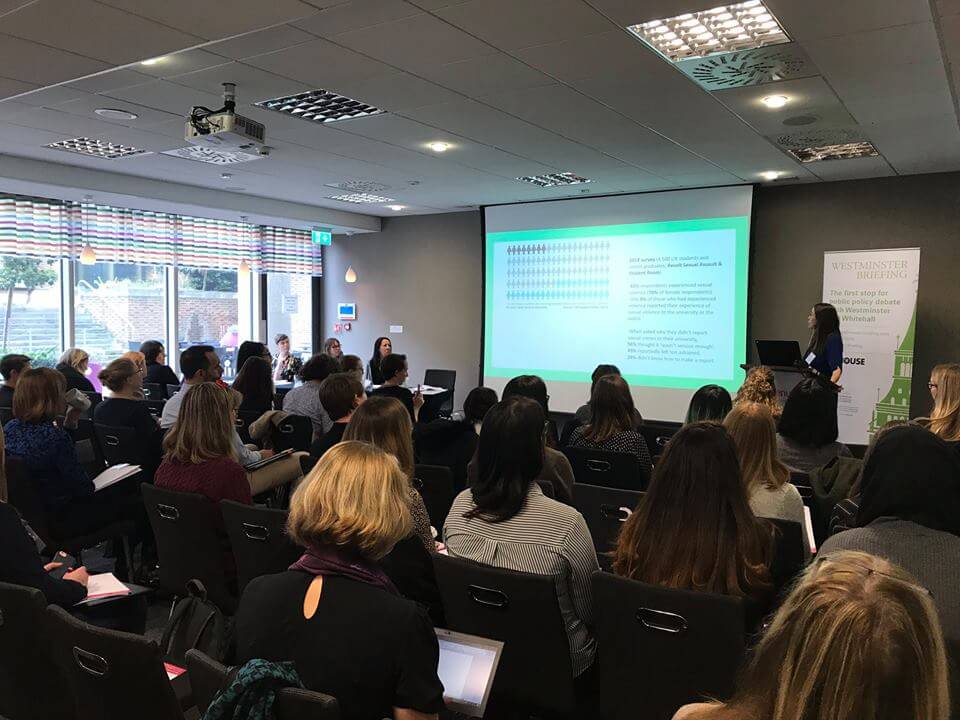

[photo credits, Scottish Women’s Cooperative]

2018 might be over but the gender pay gap is far from closed. According to the ONS, the UK’s gender pay gap in 2018 was 17.4%. This means that men’s average hourly earnings were 17.4% higher than women’s for full and part time work. Despite the fact that it is illegal to pay men and women differently for performing work of the same value, the general expense of taking employers to court (coupled with a lack of transparency about pay culture in general), ensures that justice for women is rarely served.

The historic scale of this injustice is something we must urgently consider as we move in to the new year. In her article ‘What’s to blame for the gender pay gap? The housework myth’, historian Emma Griffin demonstrates how, for centuries, work performed by women has been less valued, and paid less, than work performed by men. As such, she is able to illustrate how the value of work (whether perceived or otherwise) continues to be shaped by ideas about gender.

Following on from Griffin’s work about the history of the problem, this post will consider some specific cases of gender pay inequality. Over the course of my university research, I discovered that the Women’s Co-Operative Guild and the Air Transport Auxiliary were involved in attempts to gain greater pay equality for women. Although they remain under-researched, they illustrate how protest against gender pay inequality has a long and varied history. They act as a call to situate unequal pay in a broader context, including how it informs current debate about pay inequality in the UK.

The Women’s Co-Operative Guild set a precedent for contemporary considerations of gender equality, by drawing attention to the extent of labour (both paid and unpaid) that women were expected to carry out. For example, in 1911 WCG campaigned for housewives to receive National Insurance, arguing that ‘women who remained at home were workers, and that their work was as arduous as any other kind of work and just as valuable.’[1] This was particularly relevant to WCG members many of whom were working-class housewives without any fixed forms of external income. The WCG also campaigned for the rights of female Co-Operative employees, following the proposal of a minimum wage for male Co-Operative employees, in 1907. The women’s minimum wage they proposed was lower, for example 4s. a week for girls aged 14 compared to 5s. for boys. However, it seems that the WCG was campaigning for greater gender pay equality as a 1910 petition, signed by over 13,000 WCG members, argued that the minimum wage was ‘a step towards a living wage and the ultimate adoption of equal pay for equal work.’ WCG members used strategies such as proposing resolutions at Co-Operative Societies’ business meetings, to persuade local Co-Operative Societies to adopt the minimum wage. At a national level, after failed resolutions, WCG first gained a minimum wage for female packers, before gaining a minimum wage for all female Co-Operative employees in 1914.[2]

Almost three decades later, the Air Transport Auxiliary also took great strides to secure greater pay equality for women. ATA was a civilian organisation established in WW2 to ferry RAF planes. In 1940, ATA started employing female pilots, paying them 20% less than their male counterparts. It seems that Pauline Gower, who led the women’s section, was always in favour of equal pay; in 1940 the Marquess of Donegall wrote that he couldn’t ‘explain to Miss Gower why her girls should be paid less’, implying that Gower had already discussed equal pay with him.[3]

In 1943, Lettice Curtis became the first female ATA pilot cleared to fly four-engine bombers and Gower seized the opportunity to place equal pay back on the national agenda. After at least one failed attempt, Gower went directly to the Minister of Aircraft Production and in May 1943 ATA became the first organisation under government control with equal pay for men and women. Gower’s father was a former politician and according to some accounts, Gower threatened that Irene Ward MP would raise the issue in parliament if equal pay was not granted.[4]

ATA and WCG’s actions in the first half of the 20th century illustrate how there has been a long history of successful attempts to gain greater gender pay equality. They also demonstrate how achieving this success has been historically very difficult. Despite WCG’s mass mobilisation and Gower’s high up contacts, their steps towards greater pay equality involved failed attempts and took many years. Today, women’s salaries are generally lower than men’s while women still perform the bulk of unpaid housework. Moreover, just as we cannot understand Gower’s approach to gaining equal pay without understanding her social background, we must not underestimate how similar questions of race, class and ethnicity impact on women’s struggle for equal pay today.

Looking at WCG and ATA shows how our attempts to solve gender pay inequality are part of a long, difficult struggle. I suggest that adopting a historically engaged approach also encourages us to consider the broader context of pay inequality, revealing larger patterns of discrimination against women from all walks of life. Whilst progress towards true pay equality may be painstakingly slow, by looking back we can take strength and comfort from the huge strides made by the trailblazers who have come before us.

Rowan Cookson

Bibliography

[1] Gillian Scott, Feminism and the politics of working women: the Women’s Co-operative Guild, 1880s to the Second World War (London: UCL Press, 1998), p.86.

[2] Catherine Welles The woman with the basket the history of the Women’s Co-operative Guild, 1883-1927 (Manchester: The Co-Operative Wholesale Society, 1927), pp. 116-121.

[3] Edward Chichester, ‘Almost In Confidence’, Sunday Dispatch, 5 May 1940, p. 2.

[4] Giles Whittell, Spitfire Women of World War II (London: Harper Perennial, 2007), p.234.